I dedicate this to two people. My dear friend Arthur, who talked me into doing it.

But only kind of, so don’t blame him.

And my wife Julie, without whom I wouldn’t have the luxury of writing. Or much else.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Brits, Italians, Germans, and Puerto Ricans

Chapter 2: A Punch Up at a Wedding

Chapter 3: Love and Other Things

Chapter 4: Cars For Kids

Chapter 5: A Car (& Much More) For a Kid

Chapter 6: Doors Opened and Closed

Chapter 7: Do Over

Chapter 8: Eli Picks Up Himself and The Car

Chapter 9: Beverly Elizabeth Booth is a Modern Woman

Chapter 10: Drugs, War, Peace and a Big Party

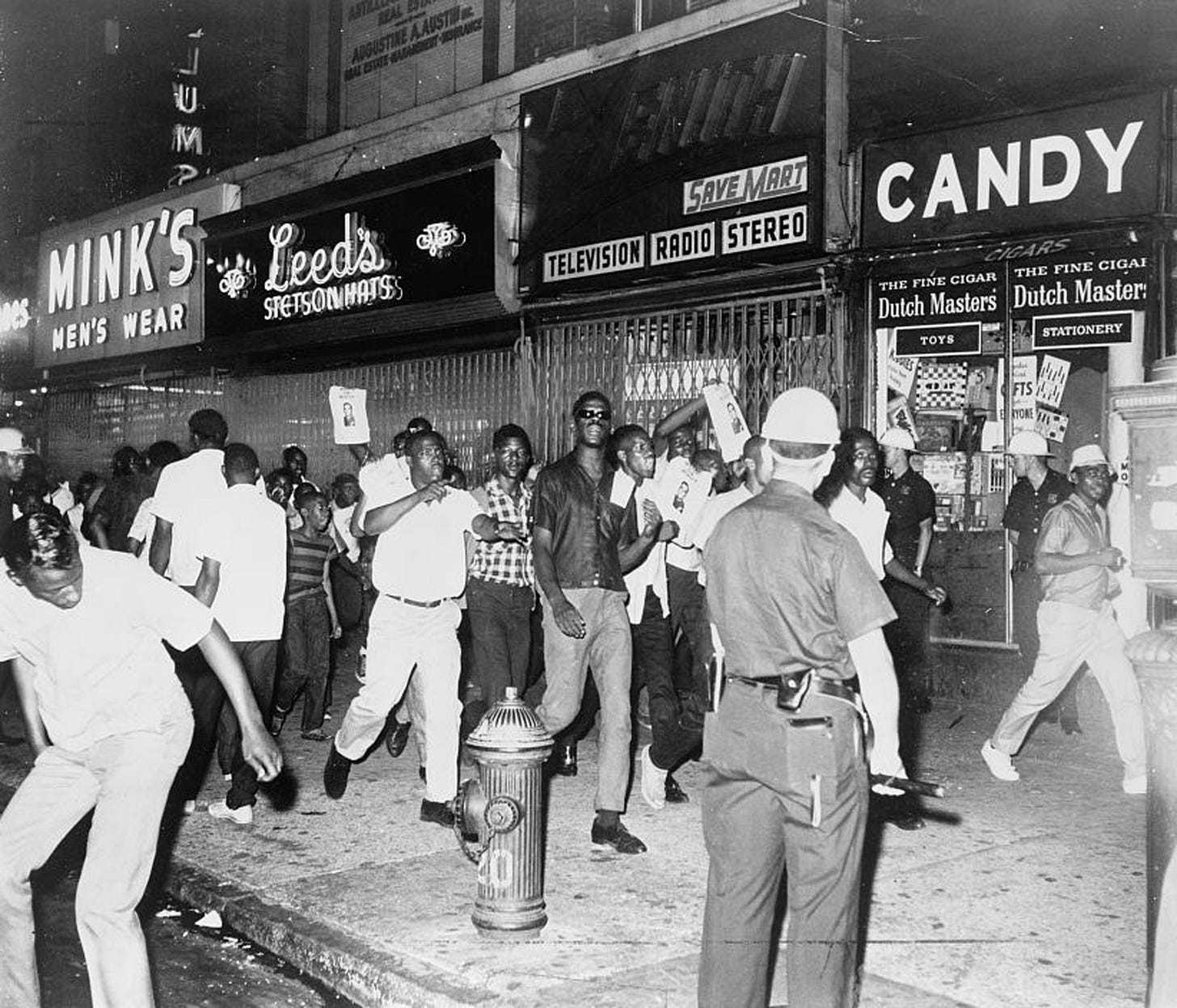

Chapter 11: Freedom and Riots

Chapter 12: Going West and East

Chapter 13: Rutger from Stuttgart

Chapter 14: Summer Games in Fall

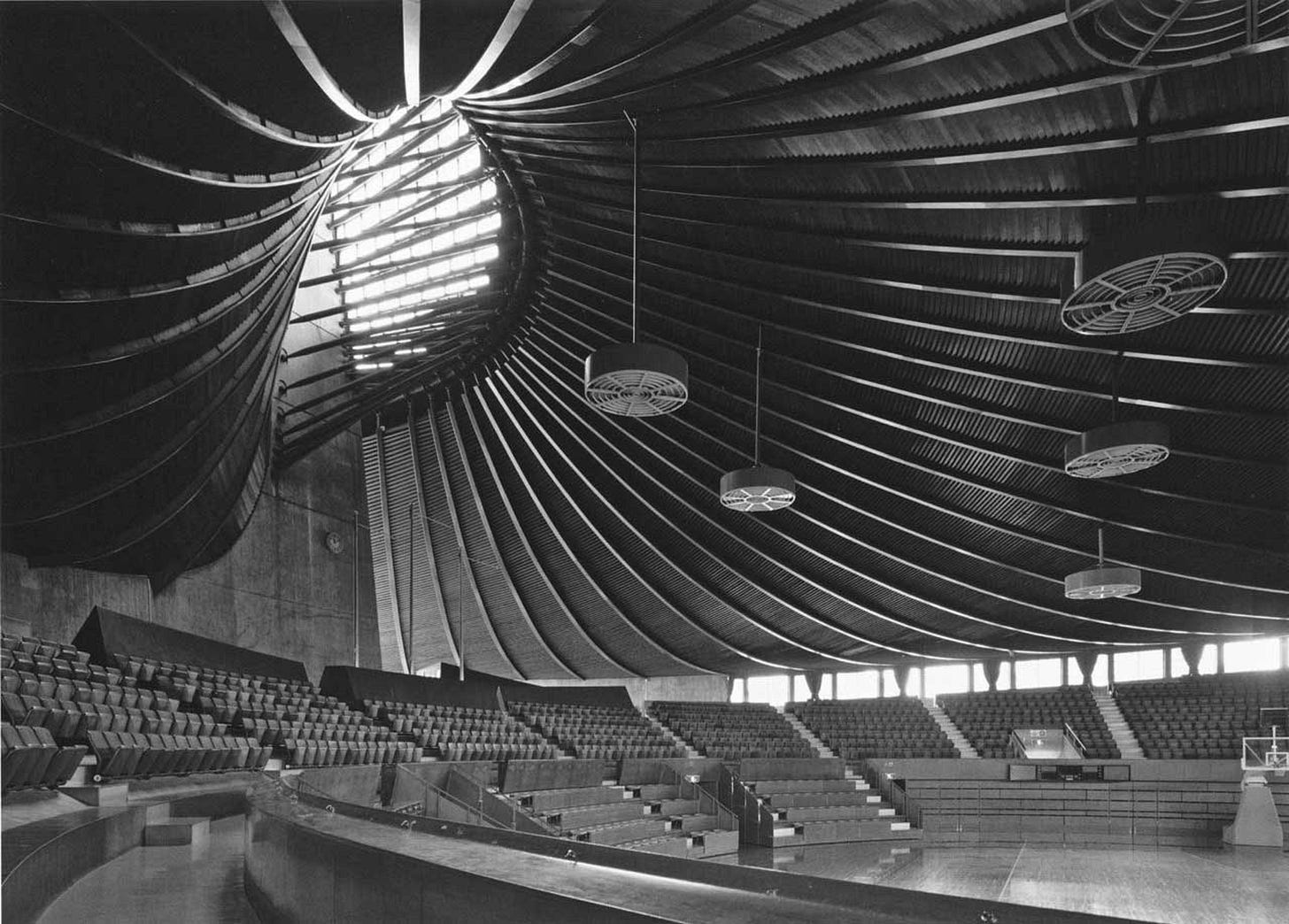

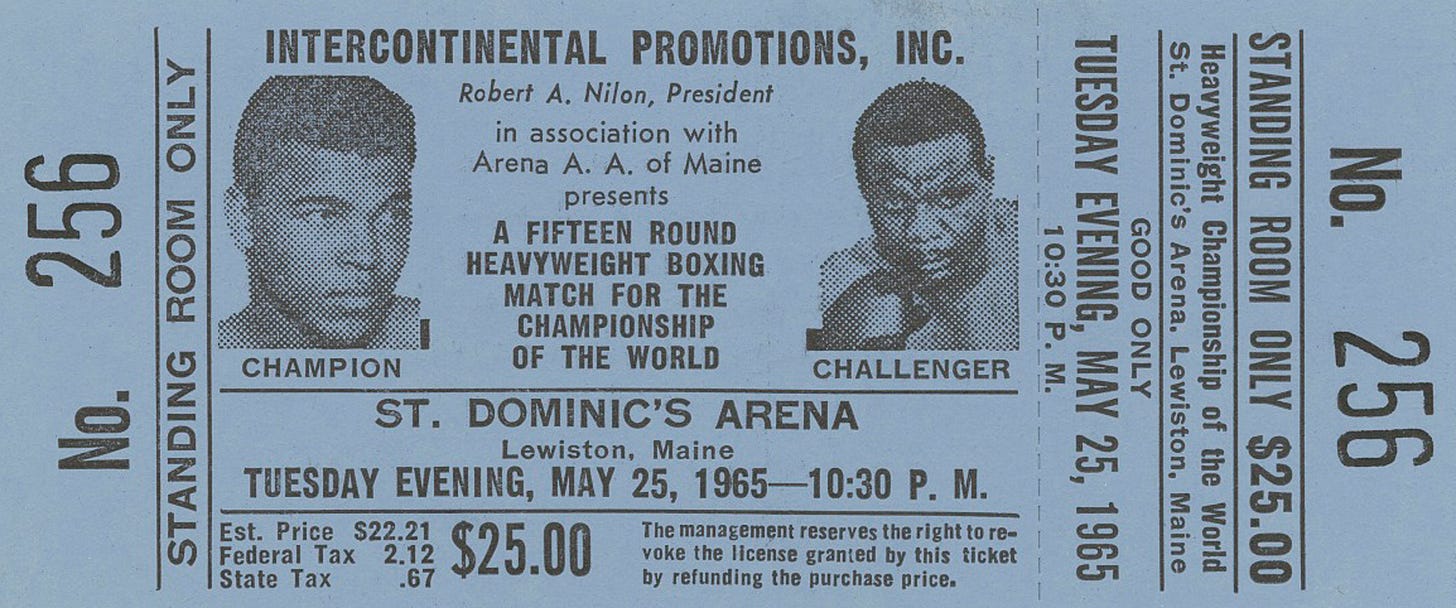

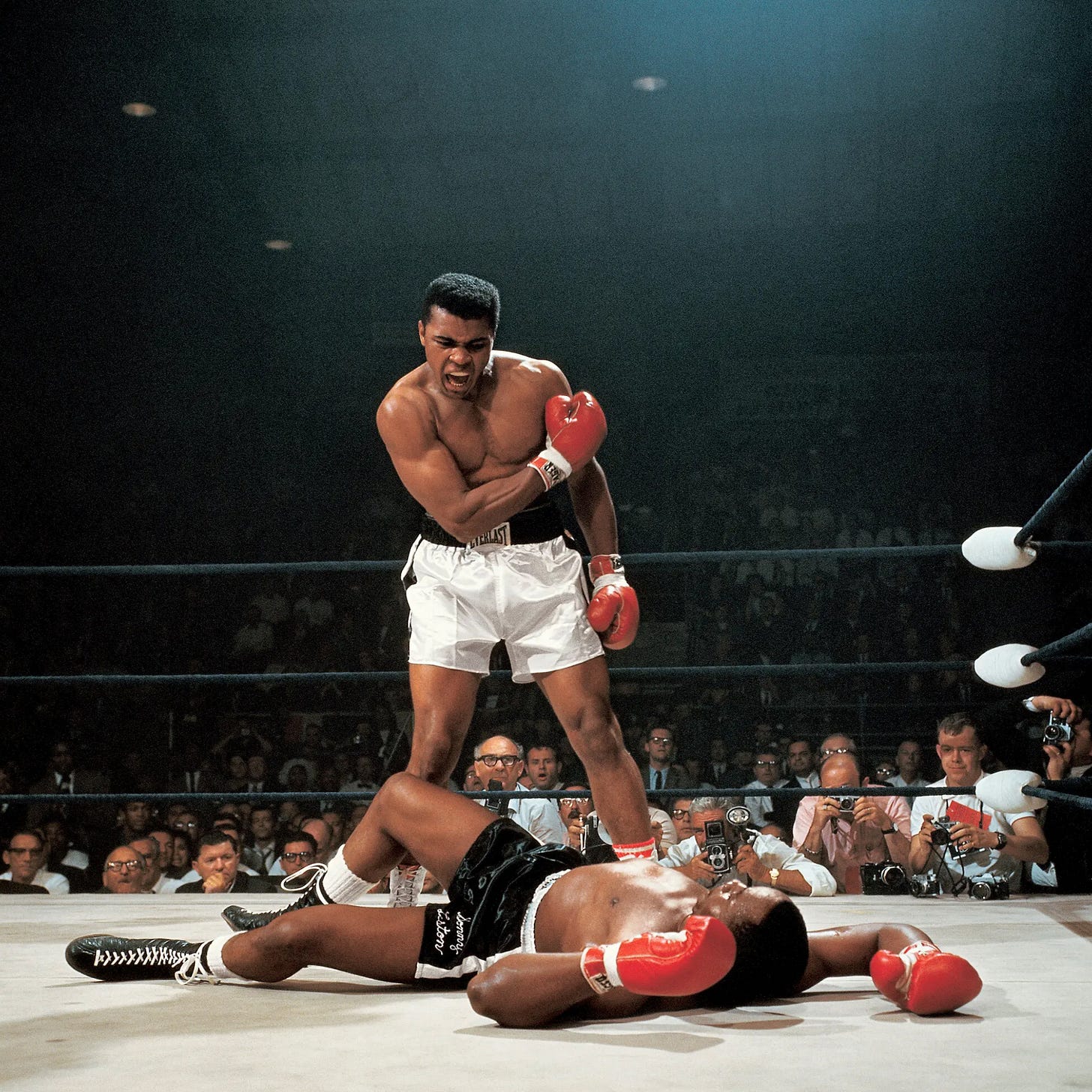

Chapter 15: 3 Days in 1965

Chapter 16: Cover Stories

Chapter 17: Fire and Ice

Chapter 18: Ben Jr Wants Liberation

Chapter 19: Time Magazine Interviews Connie in SF

Chapter 1: Brits, Italian, Germans, and Puerto Ricans

Cooking and Language School

Benjamin Elias Spencer, from just outside of London, was 19 in 1918 and serving King George V in World War I. A member of the 101st Field Company of the Royal Engineers, he had been assigned to build roads and bridges in the mountainous Dolomites, on the border between Britain’s fellow Allied Power Italy and the Central Power foe Austria-Hungary.

“Excuse me, but aren’t they called the Italian Alps?” he had asked a superior when first getting the assignment, but now he knew better.

Indeed, a year in, Private Spencer knew that and quite a bit more. First, and in no surprise for someone from Shepherd’s Bush who had been exactly nowhere, he was astonished by the splendor of the Dolomites. He had seen pictures of mountains before in school, but he found the jagged spires that surrounded him astonishing.

Secondly, in between the long days with shovel and pickax in hand, Ben had developed a talent for cooking for his colleagues. Specifically, he had a knack for sourcing local meats and cheeses and peppers and breads and making the best sandwiches anyone had ever tasted - and this from a Brit? During a war’s privations? Even the stoic locals of Val Gardena were impressed.

It helped that, over time, he had picked up quite a bit of Italian and even some German; he even could say a few words in the native tongue of Ladin. Learning languages seemed to be in Ben's nature.

During his 14 months in The Great War, he had built roads, bridges, and sandwiches and got out unscathed, although his time in Italy had a major impact. He returned home to England, but soon emigrated to the United States.

Because while he didn’t know it at the time or had even heard the word (coined by the French economic philosopher Jean-Baptiste Say in the early 1800s), Ben was an entrepreneur. He was determined to take what he had learned and do something with it independently, in a place where that was welcome, unlike in Britain.

So in 1919, Ben left Blighty for good and landed on Ellis Island and then made the short trip to Hoboken, New Jersey. It was fortuitous timing, because America’s immigration clampdowns were coming in the form of the Quota Act of 1921 and the National Origins Act of 1924. The inflow of Irish, Italians, Jews, Germans, Poles, and yes, even English was about to end.

But Ben made it to America and would live out the rest of his life at 4th and Washington, near the docks and on Hoboken’s commercial corridor. The family he and his wife Chelsea would raise there were lucky he made it.

The Wedding of Constance Spencer, Act 1

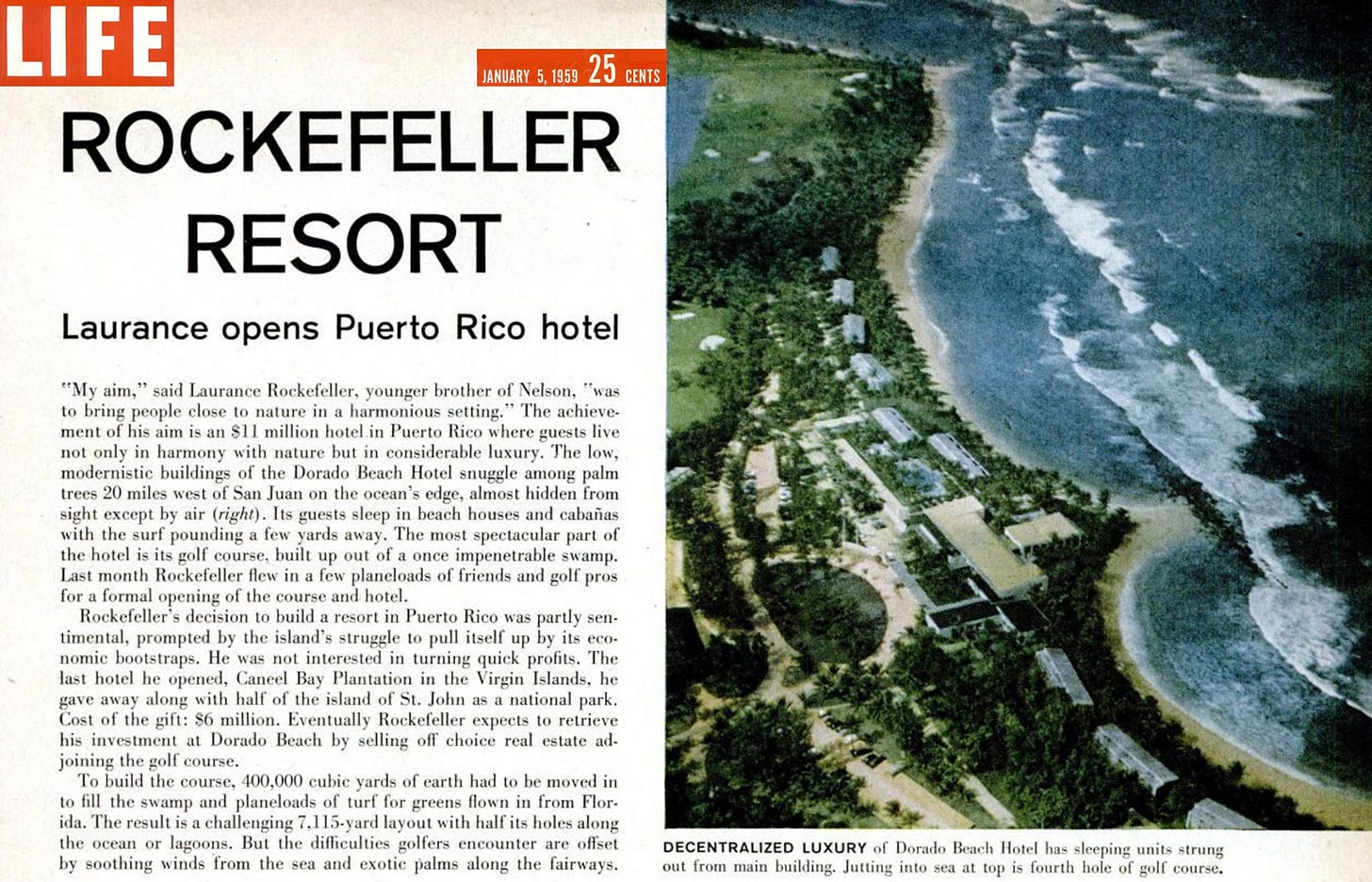

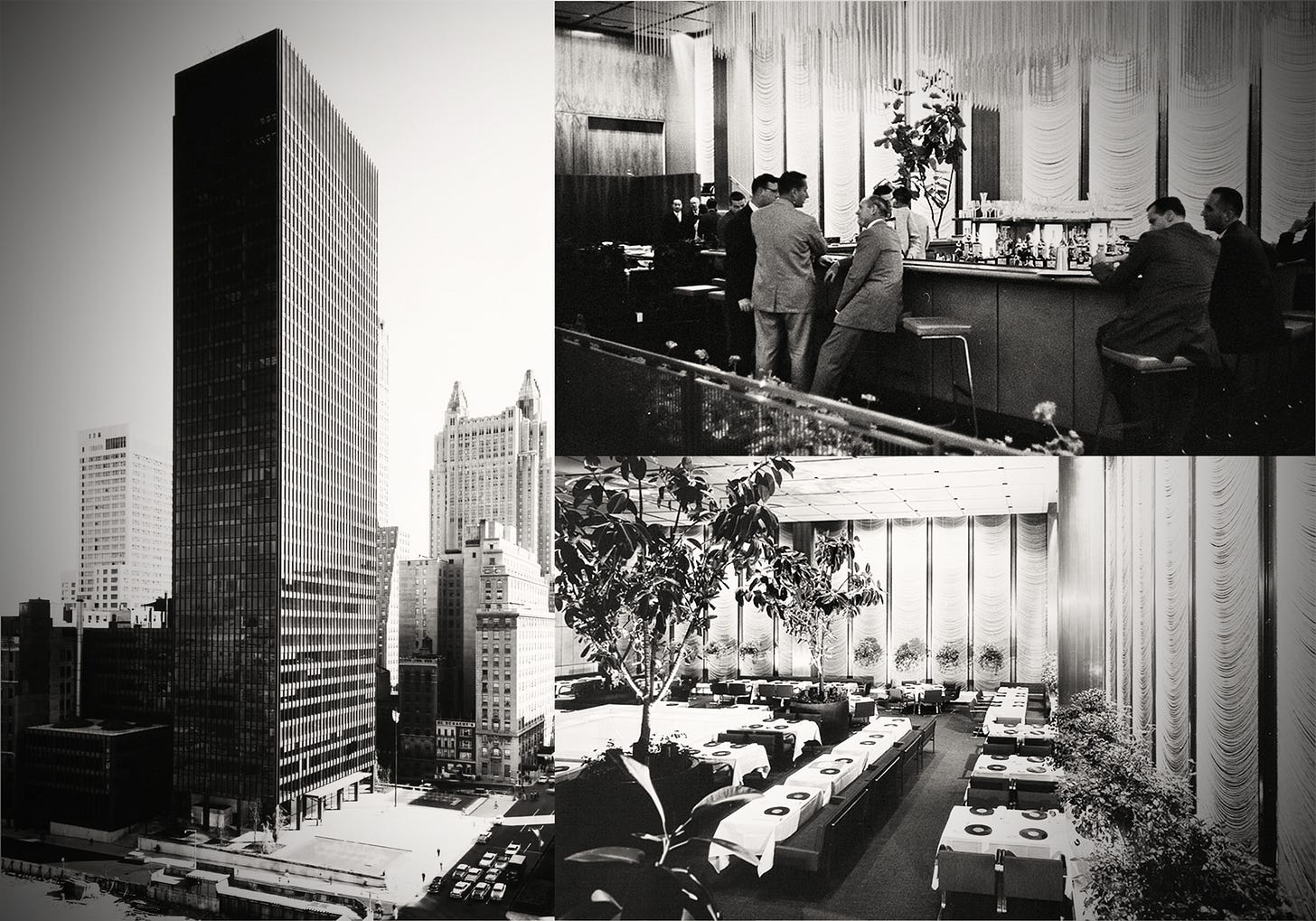

While New York State Governor Nelson Rockefeller was trying to emulate his father’s monumental Rockefeller Center with his South Mall in dreary Albany, his best friend and brother Laurance was doing a bit of building of his own.

But in far nicer places. And instead of offices, he was creating some of the world’s finest hotels.

In 1956, he opened his first, Caneel Bay Resort on St. John in the US Virgin Islands. Just two years later, he had finished his second, Dorado Beach Resort, about an hour’s drive west of San Juan on Puerto Rico. In 1964, the British Virgin Islands would get a RockResort of their own, with Little Dix Bay on Virgin Gorda. And in ‘65, Laurance sprang the incredible Mauna Kea Beach Hotel on the world; it was the first resort on Hawai’i Island.

But it was his still new-ish Dorado Beach masterpiece in Puerto Rico that was the location for the December 8, 1963 wedding of Benjamin Spencer Sr’s beloved granddaughter, Constance.

He and 38 other guests were here to see what not too long ago would have been unthinkable: the marriage of a privileged white girl from Hoboken to a Puerto Rican. It’s partly why when Constance - Connie - insisted they marry on her 21st birthday, they chose this resort rather than her gritty and gray hometown.

And of course, Alvaro Carrión was no ordinary Puerto Rican. His father, Rafael Carrión, was a founder of Banco Popular de Puerto Rico, the largest bank in Puerto Rico and one of the largest in all of Latin America. When Hoboken’s Puerto Rican population began to take off, the elder Carrión sent his son Al there to establish a branch of the family business in 1958.

It had worked out great in more ways than just financially: the Hoboken bank was where Al and Connie first met, by chance, when she stopped by for a roll of dimes. He was 6 years her senior.

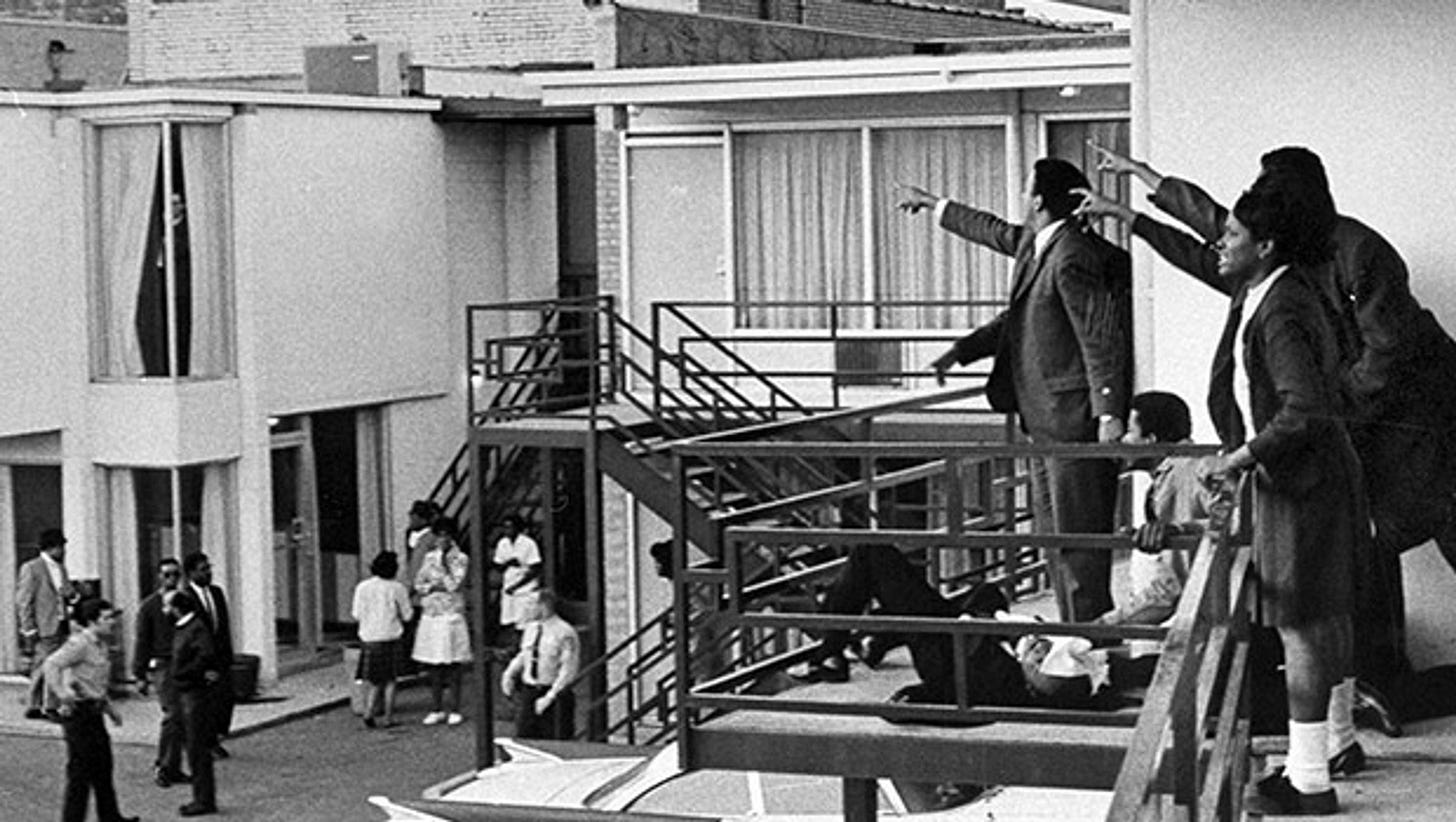

While Laurance Rockefeller didn’t need a loan (or dimes) from the elder Carrión in San Juan, he did need permission: Nothing much happened on the island without a nod from Señor Carrión, pictured here during the wedding weekend.

And with that, plus some of his cash spread liberally around the island, Laurance Rockefeller was able to build and open his Dorado Beach Resort. He did such a fine job that it soon became the place to go for the northeastern’s elite, and those wishing to appear so.

Like the Spencers.

So when Alvaro and Connie got engaged, and she pushed for a December ceremony, the Dorado Beach Resort was an easy choice. It would be perfect, they thought.

It wasn’t, as the timing turned out to be awful. Because while Connie believed it would be fun having her wedding on her birthday and that of her best friend, her fraternal twin brother Benjamin Elias Spencer III, some horrendous events meant the wedding would be dark, despite the tropical sunbeams.

First, John F. Kennedy had just been murdered in Dallas. Having happened just a couple of weeks prior, it still cast a pall over most everything. But while some of the Irish back home thought it rude she didn’t postpone, Constance moved forward. After all, she reasoned, she hadn’t rescheduled her nuptials when her Mom committed suicide. Why do it now because of Camelot’s destruction?

On St. Patrick’s Day, just 9 months prior, Genevieve Laroux Spencer, wife of Ben Jr and mother to Connie and Eli, carried out what she had threatened for years. Except nobody had paid much attention then to the always-histrionic but charismatic Gen. One of her favorite jokes about her twins was that Ben Jr and she didn’t have much sex, but when they got hammered together at The Elysian on St. Paddy’s in 1942 and did, they got two for the price of one.

In a final, horrific stroke of the narcissism she had displayed since their birth, she slit her wrists on 3/17/1963. Everyone in the family supposed she did it in one of the cars in the garage in Manhattan as a final fuck you to Ben Jr, and on the day of the twins’ conception as one to them, too.

In her own mind, Genevieve Spencer killed herself to prove to Ben Jr, Elias, and Constance what they had heard forever: They had let her down. Ben Jr with his various dalliances in Manhattan with God knows who, and the children? She had resented them from the start and could never hide it.

While Connie proved resilient in the face of this tragedy, her twin Elias (the family never called him Benjamin) fell apart. 20 and already well-versed in both the drinking arts and underachieving, his mother’s suicide had sent him on a months-long bender. Indeed, Connie almost canceled the wedding not because of personal and national calamity, but rather because of Eli’s drunken and erratic behavior.

But he had promised to behave this weekend. They were best friends and he was determined to stay sober.

The Spencers’ Tupper Lake cousins Craig and Bob Laroux were chatting about all of this on the pillow-soft and golden sand beach that fronts the hotel. There weren’t very many secrets in the Spencer and Laroux families.

It was Friday in the later afternoon, and the wedding was Sunday. Tomorrow would bring the rehearsal dinner on a 70’ sloop on the warm Atlantic, but today and tonight were at leisure for the guests.

The palms - and there were a lot - swayed in the damp tropical breeze. But the moist wind wasn’t doing much to cool the two Laroux brothers. Being snowbirds to the core, they had chosen loungers fully exposed to the sun.

“Hey, it’s too fucking sunny – let’s get some shade,” muttered Craig, as he polished off another Schlitz and muffled a burp. He and his fellow mountain man brother Bob didn’t get much tropical sun in Tupper Lake, and it showed. They were hot and red, and not unusually, they wanted to grab a couple of more beers, preferably somewhere air-conditioned. Which wouldn’t be a problem, although getting to the hotel itself hadn’t been easy for them.

They had taken the New York Central from Tupper Lake Junction in the middle of the Adirondack Mountains to Utica, connected with a train through Albany for New York, and then got themselves to Idlewild Airport. At least the flight was nonstop to San Juan on Eastern Airlines; this was a very popular route now. The two country boys availed themselves well on their first jet flight. In fact, the captain was so charmed by their authentic aw-shuckness that he walked them out onto the tarmac at the San Juan airport after the flight, so Bob could take this snapshot.

The others? As pretty much all of the Spencers and most everyone else attending the wedding came from Hoboken or very close, it was easy: There was also nonstop jet service from Newark to San Juan.

Given Ben Jr’s success, it was no surprise his daughter’s wedding wanted for nothing. Although he “only” owned a car service (as he put it), he was still one of Hoboken’s most prominent and respected businessmen, as was his father, deli owner Ben Sr.

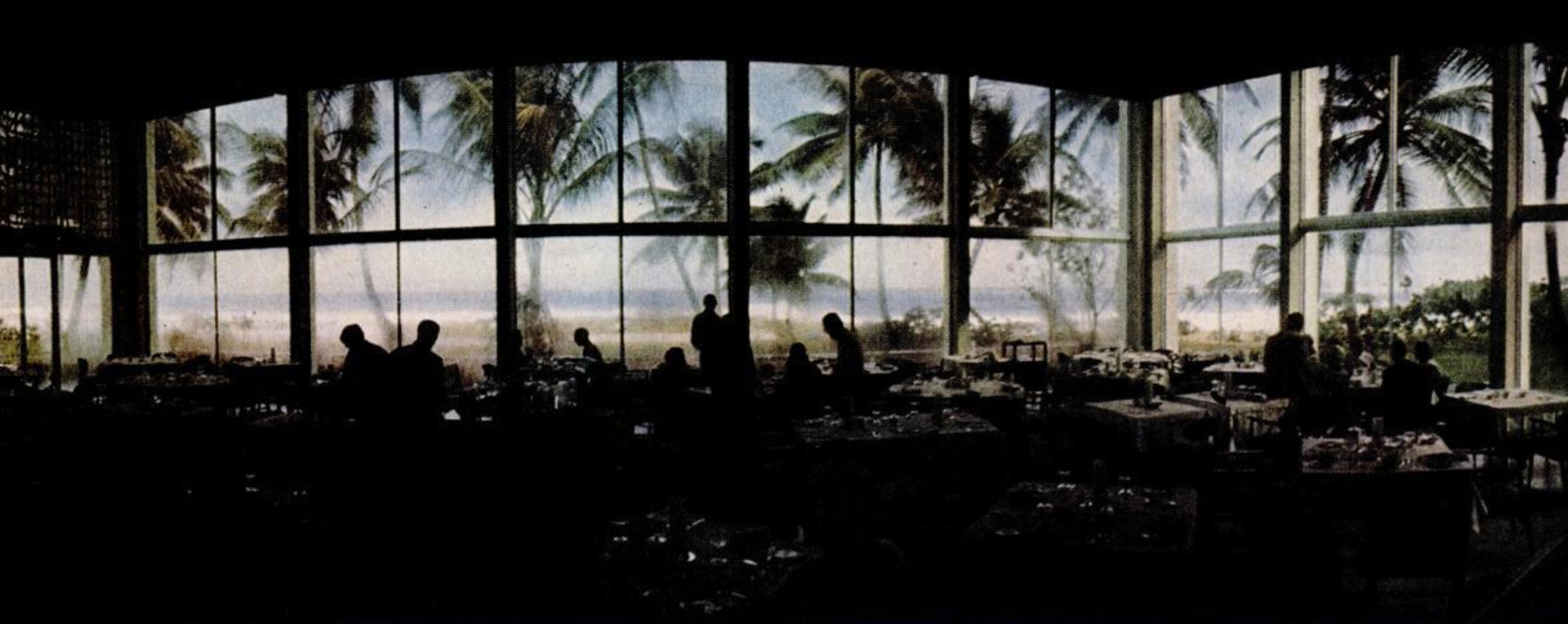

So among other things this weekend, that meant a fully-stocked, 24-hour hospitality suite. It was big, luxuriously appointed, and nicely air-conditioned. And Ben Sr’s influence was certainly felt in terms of the quality of the catering. It also had a large, furnished veranda that offered an expansive view of the beach and ocean below. Overall, it was one of the nicest suites any of the guests - some well-traveled - had ever seen.

Into this opulence sauntered the sunburned and decidedly non-opulent Craig and Bob Laroux. Knowing the family as they did, they were not surprised to find most of the family hanging around the free and expansive selection of top-shelf booze and beer. Wine? Only the French Champagne that Connie had insisted upon, although it looked like Ben Jr had bought several cases.

“Hi, buddy,” cousin Bob greeted the barman, who was clad in a crisp white jacket. The color of his coat contrasted with the deep cocoa shade of his skin, which was darker than that of the bridegroom, but not by much. Many still couldn’t get over Constance was marrying a Puerto Rican, no matter how rich or handsome.

“Or snobby,” Craig had said to Bob previously when the subject came up.

But the cousins’ real focus was getting buzzed for free on Uncle Ben’s dime. “Two double V.O. and waters, please,” and he turned and said to Craig, “Let’s get off the Schlitz and I can’t stand daiquiris.”

They then surveyed the room.

While a red rose was brought to every gathering that weekend and set on a chair to represent the missing Genevieve, the whole clan was present otherwise.

The bride and groom were nuzzling off to the side, Ben Sr dozed on a couch, while his now-widowed son sought solace from both a Jack Daniels and his mother and daughter’s namesake, Chelsea Constance Poe Spencer. Born on exactly the same day in exactly the same year, both of his parents were now 64 and had been married for 43 of them. Indeed, Connie got the idea to marry on her birthday from her parents: they had wed on September 9, 1920.

Chelsea, a Hoboken native and not from its pretty part, was her typical loving but direct self. “You are going to have to keep it together. We both know she was never right after your twins were born and it’s been a fucking roller coaster. But look - you are only 41. You have a big part of your life ahead of you and you need to pull your head out of your ass.

“Plus, you have so much pussy in Manhattan, you may end up happier.”

Benjamin Elias Spencer Jr, even after an entire life hearing it, was still taken aback by his mother’s obnoxiously foul mouth. And he simply ignored her now-frequent digs on his infidelity.

“Well, it feels awful, but in some way I am relieved she’s gone. I can only say that to you, Mom. I don’t understand my feelings.”

He looked lost. Chelsea gave him a long hug and then looked at both of her only grandchildren. Elias was thankfully drinking only ginger ale, while Connie - no surprise - was drinking Champagne and perhaps too much, thought her grandmother?

Ben Jr by now had walked away from his mother and approached the record player he had the hotel set up in the hospitality suite.

“Excuse me, sir?” had been the polite response at the front desk when he first asked, but they soon found one, and even the records he had requested. He had picked out some of his favorites from the year, and luckily a bellman found a record store in San Juan with everything. Well, luck and the motivation of the crisp $20 Ben Jr had flipped him.

Because Ben Jr loves and needs his music, especially now: Like the other diversions he now sought, music temporarily helped him forget his decidedly mixed emotions over his dead wife. He stacked the records, the needle dropped, and the party was on.

The younger among them especially enjoyed his first pick, although just about everyone tapped their feet. Like the Spencers, the music was a product of Britain.

The first record he played was the debut album from a band called The Beatles.

Chapter 2: A Punch Up at a Wedding

Ben Gets Lucky

It didn’t take Ben Spencer long to assimilate in America.

Sure, it had been a miserable crossing, and the bureaucracy at Ellis Island had taken the better part of a day. But Ben was an American now, in Hoboken. He landed in the so-called mile square city because his chums back home working the West India Docks said Hoboken was an American equivalent.

It was true. It looked different but similar as Ben took his first streetcar ride to Hoboken Terminal.

He also knew a lot of Italians and Germans had already moved there to work its docks, so his language skills were going to be a big asset. He would learn that immediately.

“Stanza in affito” was the hand-lettered sign on the ramshackle residence of Giovanni Luizzi, at 2nd and Jackson. Luizzi, fairly new to the country himself but from Italy, was stunned to hear this fair-skinned Brit speak fluent Italian on his doorstep. He naturally rented Ben the room, and although the home looked a bit dodgy on the outside, Ben was pleased to find the inside tidy and well-tended by Gio’s wife, Alessia. Hearing her name made Ben smile, as that was the name of his girlfriend in Val Gardena during the Great War. They both made him feel welcome.

Over time, Gio and Alessia introduced the affable Ben to the neighborhood. Nobody failed to gasp when this Brit spoke Italian and German in a neighborhood full of people from both places.

And then there was his cooking, and more specifically, his sandwich making. As in the Dolomites, his ability to take what was available locally and combine them to be magical was even better than his linguistics. But luckily he had both, because his unusual multi-language ability got him noticed and thus hired for day work on the docks, despite being straight off the boat.

But he hated it, and the corruption and violence prevalent there even more. He wanted out and was determined to open his own delicatessen. It was his dream, he clearly had the raw skills, and it was obvious the business was there for one. Hoboken was teeming with factory and dock workers, each needing to be fed, and not always at home. Ben was prepared, but needed an opportunity.

It presented itself at his church, uptown at Trinity Episcopal. Started in 1853, it is the oldest parish in town.

Ben, mostly out of respect for the wishes of his mother, tried to attend regularly. He was lucky he did, because one Sunday, early in 1920, his life would be changed forever. It was on that day he met Chelsea Constance Poe.

Chelsea, of British lineage like Ben but born and raised in Hoboken like her parents, was gorgeous. Thin and tall, with dark blond hair and blue eyes that always reminded Ben of the ocean, they met outside as the congregation chatted after the service. There was an immediate, and mutual, attraction.

She was beautiful, yes, but subtle? No. Chelsea got right to it.

“Hello! I’m Chelsea and you’re new here, aren’t you?”

“I am,” Ben said, a bit flushed because he felt the electricity already.

“Well, why don’t you ask me out so I can show you around? I’ve lived here forever, and I know everybody. Even the nitwits and rubes, who I’ll kindly point out!”

Ben couldn’t resist her blunt and effusive charm. She was direct in a way no British girl ever could be and he couldn’t get enough.

They started dating, and Chelsea, at 21 already no stranger to the bedroom, brought him into hers after only their 4th date. Ben was no virgin either but had never experienced what he did with Chelsea before.

They were lying in her bed afterwards when he asked her a question.

“When is your birthday?”

She giggled and said, “Are you afraid I’m not old enough?”

“No. I’m serious. Mine is September 9, 1899. Four nines! When is yours?”

“You kiddin’ me? No shit? MY birthday is September 9, 1889!”

Ben said, “Let’s get married,” and that was that.

An honorable man, he proposed even before knowing her father would rent them, dirt cheap, a vacant flat he owned, at 4th and Washington. Tragically, the couple living there previously had succumbed to the Spanish Flu, 2 of the 160,000 that died from it during the first six months of 1919.

But Chelsea and Ben were very much alive, and not only in the bedroom. They married and moved in during June of 1920.

Even better was the vacant storefront on the first floor, that Mr. Poe said Ben and Chelsea could rent, too. For $1 a month, “Forever,” he said then, and he stuck to it. That and Ben’s skills made it work, even through a depression. Chelsea was her father’s favorite, and it meant the world to have his little girl nearby and safe.

And married to a proper British gentleman, a decorated veteran of the Great War, and a real go-getter. But everybody, including Mr. Poe, doubted an Englishman could open a successful delicatessen in Hoboken. Even if he did speak Italian and German, it was common knowledge the English can’t cook.

“Horsefeathers,” Ben always said whenever his cooking acumen was questioned, and he set out to prove everyone wrong. Which he did and his shop became a Hoboken legend for decades.

Soon, Chelsea gave birth to their only child, Benjamin Elias Spencer Jr, on October 22, 1922. He was born and spent his early years above the store, in an apartment just big enough for the 3 of them.

One of his earliest memories of the family flat was of his 5th birthday party, and hearing his mother, tipsy on bathtub gin, snorting to friends, “How screwy is that, huh? 9/9/99 for me and Ben and 22/22 for our kid! Fucked up if you ask me!”

Nobody present had previously heard the term fucked up and pretended not to hear it now. In 1927, people still didn’t swear quite the way Chelsea did.

A Großer Mercedes

It was over 40 years later that Ben Jr, on his 41st birthday, bought himself a giant present. And maybe some piece of mind.

Although he was not superstitious, his parents’ and his own birthday’s symmetry made him a closet numerologist, and he often tried to make his largest purchases or important decisions on dates with 9 or 22 in them. And this was both.

But the number on his mind today was not 9, or 22, or even 41. It was 600. As in a Mercedes Benz 600 Pullman limousine. Ben Jr, after years of big success owning a fleet of Lincoln limos in Manhattan, had just walked out of the Mercedes Benz dealership there, having written a $5,000 deposit check for something far different. But just announced, it would not be until early 1964 that he’d take possession.

For now, all he had was a catalog.

And he corrected himself: Although he’d been a Mercedes guy since seeing them during his time in Stuttgart in World War II, the car was no self-indulgent gift. He had originally decided to buy it as an image-builder for his limousine business: It could put them in a new league, and gain them access to the elitist of the elite in Manhattan.

It was also a needed distraction from Genevieve’s suicide 6 months prior. The fact that she had gone to his garage in Manhattan and bled out in the back of one of the ‘59 Lincolns she hated so much had shook him and left him a confused mess.

Still: Buy the most expensive car in the world? $25,000 was an outrageous sum of money, no matter how impressive the car.

And that was on top of Connie’s wedding, coming up in December in Puerto Rico. He had tried to ignore the crazy estimates, but what could he expect, having signed off early on the concept of a wedding at a resort owned and operated by a Rockefeller?

But what disturbed Benjamin Spencer Jr the most was the real reason he had purchased The Grand Mercedes.

He mostly wanted to bribe his son, who he knew he had to fire after the wedding. Now a year removed from the car accident and expulsion from FDU, things had only gotten worse. Eli often showed up late for work to the family garage, typically smelling of the rye he drank the previous night.

It couldn’t go on and Ben Jr was going to give Eli a most expensive gift as part of a plan to straighten him up. And keep him quiet.

The Wedding of Constance Spencer, Act 2

The rehearsal dinner had been spectacular; Rafael Carrión had spared no expense for a proper party for his son and new bride, and it had been comfortable and gracious. But now it was over, and they were all off the yacht.

While Al and his father smoked cigars and drank Ron del Barrilito rum on the terrace of the hospitality suite, the Spencer twins Connie and Eli took a walk on the moonlit beach together. They hadn’t had much of a chance to talk alone, but both knew the wedding was a turning point in their relationship.

Both would turn 21 tomorrow, and although similar in so many ways, as they aged into adults, they had chosen different paths. Connie had taken the smooth one.

A looker like her mother and blessed with her father’s meticulous attention to detail and grandfather’s knack for languages, she was an honor student and nearly perfect child. Marrying the filthy rich son of a banker with homes across the Caribbean seemed like more of the same. Although some were aghast, nobody being honest back home could say the young Alvaro was anything but respected.

After returning from their brief honeymoon in Buenos Aires, she’d be finishing up her Mechanical Engineering degree at Stevens Institute that spring. Both she and Alvaro were then planning to take off the fall of 1964 and visit Tokyo for the Olympic Games, followed by a tour of the rest of Japan. She half-jokingly told friends it was payback for marrying in one Spanish place, and then honeymooning in another.

Connie had run varsity track at Hoboken’s Demarest High School and had also studied Japanese history as an elective at Stevens. Indeed, she had chosen it over MIT or Rensselaer because of its self-proclaimed “liberal-technical" focus. The fact this historic school was an 8 minute ferry ride from Manhattan didn’t bother Connie, either. It was fitting her father’s company was called cosmopolitan.

Elias Spencer’s ride through life thus far had been much rougher, and mostly by his own doing. Just as smart - if not smarter - than Connie, he was also as attractive as she and never wanted for girlfriends. But Eli’s problem was two-fold: He never applied himself, and he loved to drink.

That had caused problems since he was 14, and it got worse at the end of high school and into college. After they both graduated from Demarest, she the salutatorian, Elias with barely a B average, he enrolled at the bucolic but academically pliable Fairleigh Dickinson University.

In an incident that got him expelled in late 1962 and left a club member with a permanent scar, Elias drank too much at a club rally and cracked up the MG Midget their father had given him. His buddy Brian was cut badly by some flying glass, but was OK other than the scar on his forehead he’d have forever.

Eli was tossed out of FDU soon thereafter and announced he was going to “cool out” for a while.

So walking with his sister next to the roar of the ocean on December 7, 1963, Eli Spencer, nearly 21 and with every advantage in the world, was living with his parents in Hoboken, and cleaning limos at his father’s garage for rent, meals, and pocket money.

“What happened to you, Eli? You always wanted to have fun, but what changed? You’ve gone crazy since March and Mom, but you were very angry before then, as far back as when we were seniors. What’s the matter? It’s nice you’re sober right now, but everyone is worried about what you’re going to do next.”

“I hate Alvaro.” Eli was not lying, although not answering the question, either.

“What?” Connie, for whatever reason, always sought her brother’s approval. She wanted the two of them to get along - maybe even be close. But Connie knew the problem.

“Jesus fucking Christ, Connie, he has never been friendly to me. I am your twin, we’re very tight, and I’m not going anywhere, yet Al barely speaks to me? He’s never asked me one thing about me or our family, not once. Don’t you see that?”

Connie knew it. But somehow, she didn’t care, or at least pretended not to. Her Alvaro was an attempt to elevate the underprivileged. Sure, Al was filthy rich, but many that looked like him didn’t even get a chance. Connie - the idealist - would change the world by showing it was perfectly acceptable in 1963 for a fair-skinned upper class white girl to marry a Puerto Rican. She also thought he looked like a darker, younger, and more handsome Desi Arnaz, so there was that, too. But whether she genuinely loved him was her secret alone.

Connie sat there in silence for a moment. She didn’t like conflict, but she pushed back now.

“This is your insecurity, as usual, Eli. He’s a very smart and successful businessman. He comes from a great family, and you are telling me you’re acting so crazy because of who your sister is marrying? Bullshit.”

She was wrong, because Alvaro was a pompous bore. Yet she was correct that there was something beyond their mother’s suicide deeply troubling her twin brother. And the fact that Connie hadn’t used the word “love” with her best friend Elias in describing her feelings for Alvaro went unsaid, but not unnoticed.

The next day, Connie got the wedding of her dreams, until she didn’t.

Her twin brother Eli went off the wagon at the lavish reception. It was bound to happen, as he and his Tupper Lake cousins were renowned for debauching together at family events. But while those were typically joyous and festive moments, the reception got ugly, because a sodden Elias decided to take out his angst on his new brother-in-law.

“You know what, fuck you, Al. Why don’t you ever talk about anyone but yourself? Do you know you’ve never once asked me a single question about myself? Or Craig or Bob or anyone else I know? You’re my brother-in-law now, but you’re no brother. But you are a dick. A big, Puerto Rican dick!”

Alvaro had tried to ignore Elias, slurring badly now, as the family looked on; this was upsetting and surprising, but not really.

Suddenly, Alvaro slugged Eli square in the stomach and then shoved him against the bar, and shouted, “You are a booze hound and a fucking white nigger!”

Separated by the Laroux brothers and a shrieking Connie, Elias and Alvaro never spoke again.

The record player in the suite, somehow left on throughout the drama, happened to be playing something appropriate.

“Elevator to the gallows, indeed,” thought a somewhat bemused Ben Sr as he shuffled off to a waiting valet with a golf cart that would take him back to his suite for the night. He’d seen enough.

They all had.

Chapter 3: Love and Other Things

A Closet, A War, A Wife, A Son, A Daughter

On December 8, 1941, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Congress declared war on Imperial Japan after their attack on Pearl Harbor. While it was a terrible time in America, and had been for quite a long time, the Spencer family had thrived.

Spencer Specialties was by now a Hoboken institution and famous for its sandwiches, for which people came even from Manhattan to enjoy. Benjamin Spencer Sr was rightly proud of what he, Chelsea, and their son Ben Jr had built. It was a true family business, and suffice to say, it was a good thing to own a food shop of any kind when others were going hungry at various points during The Great Depression.

Indeed, the Spencer’s prospered to the point where Ben Sr could buy a large brownstone apartment near 11th and Hudson during the dark days of 1932. Here’s Ben Jr’s pal Larry Weinberg outside, just a few years later.

While it was now a several block walk through Hoboken’s grit to the shop, vs one chilly flight of back stairs, the 3 of them, father Ben Sr, mother Chelsea, and Ben Jr loved all of the space and newness. Their gracious 6 room apartment would welcome many Spencer family members, immediate and otherwise, in the coming years. The property never left the Spencer’s, and it, joined later by the Mercedes, became touchstones across generations.

From his earliest days, the younger Ben demonstrated not a talent for the culinary arts but rather, management. The family still laughs at the irony of him as a child pretending to run a taxi business when he was 10.

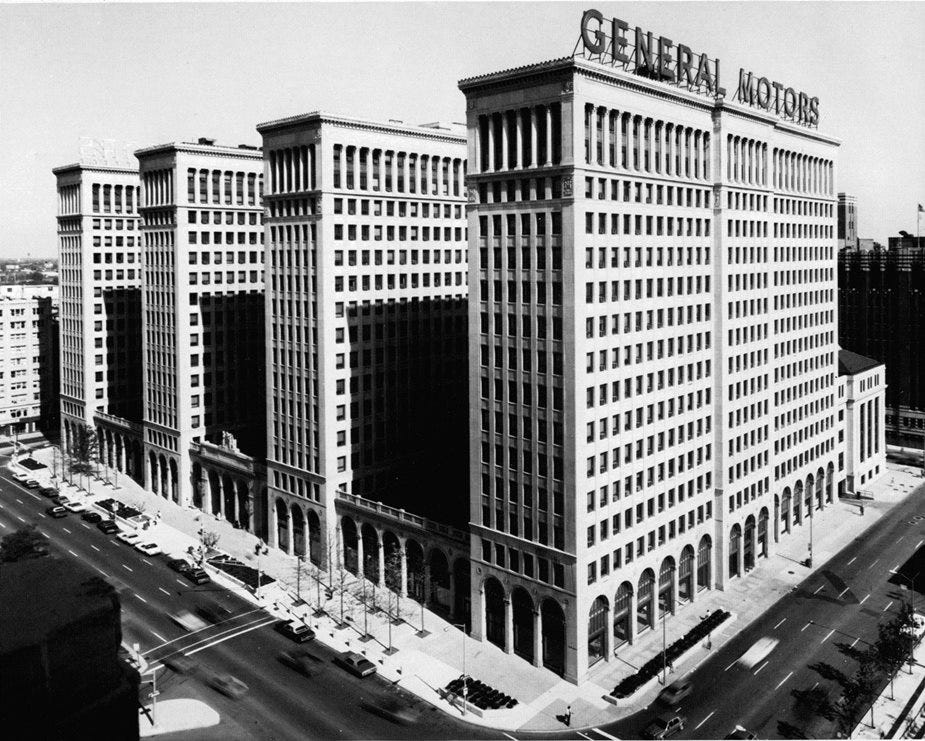

Indeed, as early as twelve he began making organizational and operational suggestions at his father’s deli. This evolved as Ben Jr matured to the point where his father often let him run the shop by age 16. With a goal of going to booming Detroit and joining General Motors, upon graduating from Demarest High School, Ben Jr enrolled at Rutgers University, in its business school.

Ben Sr missed his son at the shop, but Benjamin Elias Spencer Jr excelled at Rutgers, educationally and socially. With his stylish clothes and fastidious manner, Ben was a trend setter on campus. He made many friends, and it was with one in particular where Ben Jr found a part of himself.

Because at Rutgers, at age 18 in the late fall of 1940 and in his dormitory, Ben Jr lost his virginity.

But this time, it was to another man.

Given the era, it was something that happened with no courtship and its participants pretended it didn’t occur in the first place. Indeed, Ben suppressed his desires then, and with varying degrees of success in the coming decades. He did not wish to be branded as mentally ill and tried to forget how he felt.

So that’s how he came to be holding hands with his girlfriend Genevieve Laroux as they walked across the brisk courtyard in front of the business school, where they had met 9 months prior. Now there was a courtship - the perfectly dressed and mannered bisexual Ben and the unpolished yet charming Gen from the Adirondack mountain town of Tupper Lake. Ben and Gen dated exclusively from the get-go and Ben did it with a smile on his face.

Gen, on her own for the first time from her cloistered Catholic upbringing, was as batty in bed as she was elsewhere and it attracted even a confused Ben Jr. Well, that and the can-do attitude of a mountain girl combined with a sporty Gallic look true to her heritage. They had already talked about getting married when they finished their degrees. She knew nothing about his sexual past, or future.

They were done with classes for the day when the news began to spread on campus of the awful attack. It was about 2:30 PM. They clutched, wept, and looked east towards New York City, wondering if Germany was in cahoots with Japan and if their U-Boats would start mayhem here.

That didn’t happen. But the attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s involvement in World War II because of it meant college was going to be delayed for Ben and Genevieve.

Permanently.

And while one would prosper in service to his country, the other would use it as the first of an endless string of grievances and disappointments about which she’d harangue those around her for the rest of her troubled days.

In short order, he was drafted and told to report to Fort Dix beginning the third week of April of 1942 for basic training, in advance of being sent to the European theater of operations. He had dreamed of visiting his ancestral lands of England and the mountains of Italy where his father had been, but not this way.

The couple chose to marry before Ben’s deployment. That occurred on March 17, 1942, in a simple ceremony in Genevieve’s hometown. Although British with no Irish heritage, they still chose St. Patrick’s Day, for good luck.

With the war effort ramping up and not wanting anything showy, they married in the recently weatherized - and quite luxurious - Adirondack camp of the Laroux family. Directly on Big Wolf Pond, outside of Tupper Lake proper, the wedding was small and subdued. Which made sense, as the groom, after a brief honeymoon in nearby Montreal, would be going off to fight a war, and might never come back.

Even though sex by then was nothing new, they still enjoyed themselves - even Ben - on their wedding night, spent in the cozy guest cabin on the property. Indeed, they had so much fun, it resulted in a pair of fraternal twins, birthed by Genevieve alone but for a midwife. Her husband was thousands of miles away and would not learn of his children’s arrival until just before Christmas.

In fact, Benjamin Elias Spencer III and Constance Anne Spencer, born December 8, 1942, didn’t meet their father until he returned in 1945 to a more-than-grateful nation.

Their mother, left to fend for herself with two newborns, was not as grateful.

Alvaro at The Alvear

Connie tried to put the awful end of their wedding reception out of her mind as she and Alvaro were driven from the Dorado Beach Resort to the San Juan airport. After all, they were off to honeymoon for 7 nights at the best hotel in Buenos Aires, and one of the best hotels in the Southern Hemisphere, The Alvear Palace Hotel.

Knowing they were going to be spending a couple of months in Connie's pick of Japan next fall, she happily agreed to keep the Spanish thing going for their honeymoon, especially after Al showed her this article from a magazine he swiped at the barbershop.

Also, Connie, even as a child, loved fine hotels, so that, and a chance to continue practicing her Spanish in a city reputed to be the "Paris of the Americas" all sounded ideal. Like her grandfather, she picked up other languages quickly; Spanish was her 4th, after English, Italian, and German, the latter two being a constant connection between her and her Grandpa. And if one considered the rough Japanese she was picking up as part of her Japanese studies at Stevens, she was closing in on 5. That was another motivation for the big trip next year: She had a goal of becoming fluent in that tongue, too.

It was the day after, December 9, 1963, and she had hoped slugging her brother and calling him a name would put an end to Al’s bitching. At the time, she honestly felt they could build a life together. After all, they had everything going for them.

But he wouldn’t let it go and she was already tired of his complaints about Elias.

“Connie, I am sorry. But he is a boozing playboy that has wasted every chance your family has given him. I don’t know if I’ve ever seen him serious about anything. It’s all just a big party to him and I don’t like it. And he seems be getting worse.”

Connie knew he was right, at least partially. But her twin and best friend was a lot more than just a well-dressed barfly, and she knew instinctively as his twin there was something deeply troubling him beyond a predilection for gin mills. She also knew he had what it took to turn it around. Indeed, Connie knew Elias in ways that her handsome Puerto Rican prince never could or would. She’d later recount that his lack of empathy had been the earliest red flag.

Thankfully, they were distracted by the journey. The incessant roar of the DC-7’s props precluded much conversation of any kind for the hop to Miami. They were then lost in the bliss of 9 hours of Pan Am’s First Class service on the 707 jet ride to Buenos Aires.

There was a refueling stop in Caracas, but they got to Buenos Aires and Connie hoped a week in what some were calling a new world capital, and a Spanish one at that, would please the moody Alvaro.

Ironically, it was a Lincoln sedan that transported them from Pistarini Airport to the hotel, but it went unmentioned. Their car pulled to a gentle stop beneath the portico of the imposing Alvear Palace Hotel, and the newly-minted Mr. And Mrs. Alvaro Carrión emerged. He was in an impeccably tailored gray-blue Brooks Brothers suit and she a Chanel ensemble the color of champagne. The space, comfort, and service on the plane had made all the difference.

“I feel great - and only 9 hours!” exclaimed Connie, hoping to set the right mood. Jet service had cut the trip time between the Latin American capitals by more than half.

A bellhop rushed forward, tipping his cap with a "Buenos días, Señor y Señora Carrión!" as Al passed him a crisp American dollar bill. The hotel was expecting them, and had rolled out a literal red carpet: Buenos Aires was actively seeking to attract skilled, highly professional businessmen like Alvaro, but especially his father, Rafael - and their businesses. A branch of Banco Popular de Puerto Rico opening in BA (as everyone called it) would be a win all of the way around.

Truth be told, it was the reason Al had suggested BA in the first place; it wasn't just a random magazine article - he hoped to make some banking contacts. His new wife would learn he often conveniently omitted facts when it served him.

Connie removed her sunglasses, and focused on the grand Belle Époque façade with the appreciation of the engineer she would soon be. The Alvear Palace stood as a monument to old-world European grandeur transplanted to South American soil, while the Carrión’s were a new-world equivalent, at least for a week.

They checked in, and were not surprised at the ongoing expressions of condolence regarding Kennedy’s assassination. Nor were they surprised Connie’s father had sprung for a nice suite for them. There was even a bottle of Champagne on ice awaiting, from the same house as at their wedding. Fresh flowers, too. Ben Jr, as usual, had thought of everything.

After being tipped an extraordinarily generous $5 by Al, the bellman left and they immediately had sex on the suite’s bedroom’s plush bed. He was a stud, but Connie was already wondering if that, his money, and his thin veneer of charm would be enough.

After a nap, that night it was a feast of some of the best beef either of them had ever had. The wine, which they were told was called “Malbec,” was a perfect complement. “It’s actually one of the 4 Bordeaux varietals,” sniffed Al, who was more of a dilettante than Connie wanted to believe.

“I think there are 5, 6, even, if you include Carménère,” corrected Connie, who then ordered another bottle as a diversion. She was her father’s daughter, and while young, already sophisticated, and not just in languages and engineering.

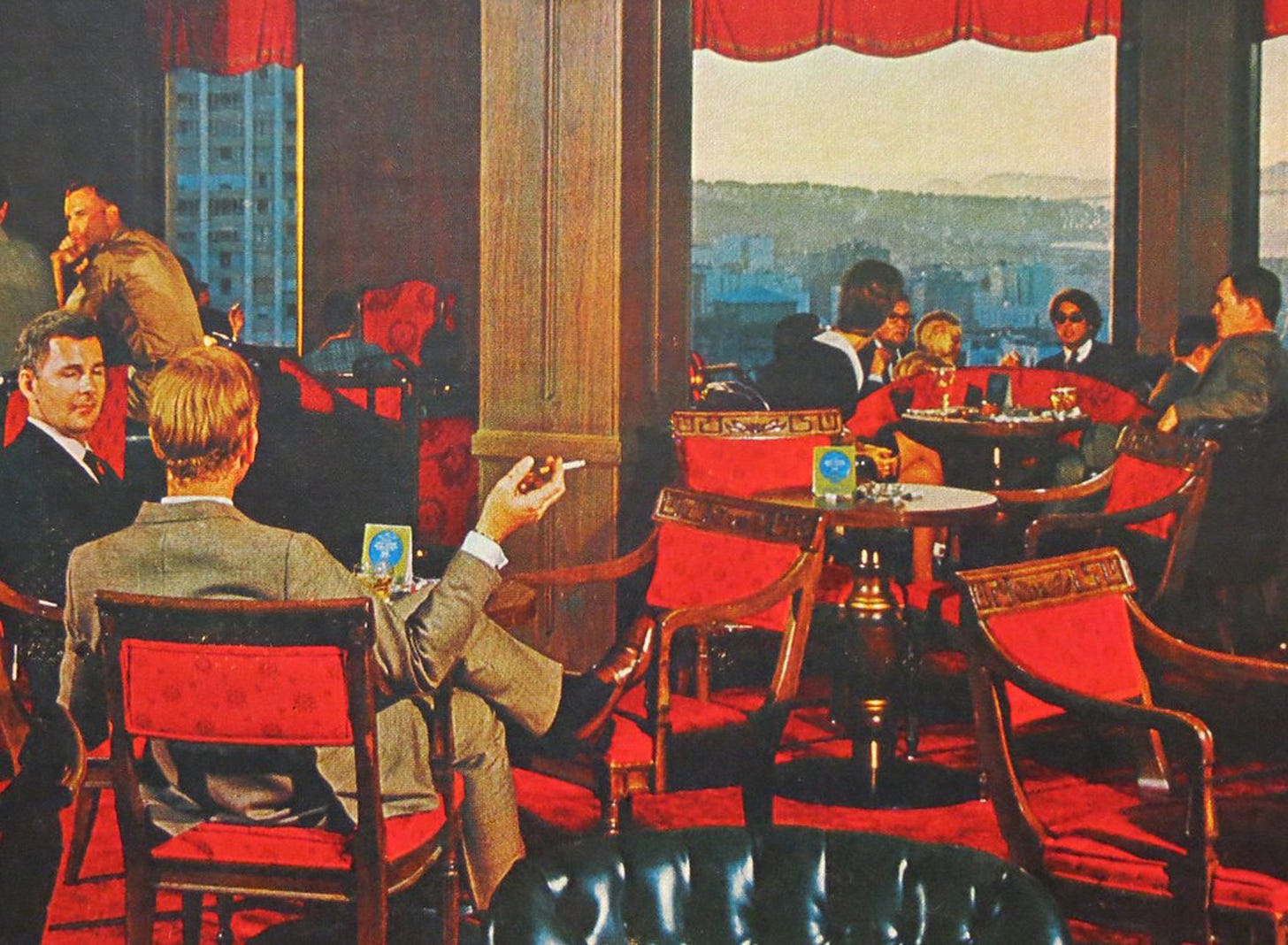

After dinner, they retreated to the hotel’s luxurious bar for a cordial. There Connie witnessed his problem in toto, which she was beginning to understand might be fatal in terms of their marriage.

Actually, Connie thought, there are two problems. One is how he always talked down to others, and no more so than with fellow Latins who happened to be waiting on him. He had done it at the Dorado, and he was doing it here.

He had an attitude just now, ordering a B & B from a bartender who had seen Alvaro’s type before, but was still gracious. Earlier, he had sneered a crack in Spanish that Connie didn’t understand when he dressed a barman down for having the audacity to serve his otherwise perfectly prepared martini with only a single olive.

There would be a similar scene at the bank the next day when they went to cash some traveler’s checks, and seemingly every other time Alvaro had a chance to show off his wealth and machismo. Connie found it tacky and rude.

But the bigger problem was his personality: He didn’t have one, or more accurately, the one he possessed was defective. While handsome and very smart, Alvaro simply didn’t take any interest in others.

While that didn't do much for him socially, it also hurt him in business, like that night over cordials at the bar. But neither Alvaro nor Connie would ever know.

Because Alvaro never learned that the Brit he was chatting up was in fact on the board of directors at First National City Bank in New York City. Who was looking for a Latin partner to enter booming Argentina and Brazil. He knew about Alvaro, his father, and their bank, and had the Argentinian government’s blessing to get a deal going.

It was no accident he was in the bar in the first place, and while he could have met Alvaro in New York, the "Citibank" executive wanted him at ease. And it was also near the government officials who would have to be bribed.

But Alvaro hadn’t asked the gentleman about his own line of work, and instead droned on about himself and his own banking prowess. The executive barely got a word in, and Alvaro hadn’t bothered to see the Englishman’s growing unease with the conversation in general.

The man left, finding Alvaro so off-putting that he would choose rival Banco Santander for his bank's South American partner. The Carrión family bank, Banco Popular de Puerto Rico, would remain a bit player in the region - and never do deals with Citi in New York, either - in large part due to Alvaro's insolence. But he hadn't noticed.

Much like he didn’t notice Connie’s unease, in the bar that night and elsewhere.

With it not even a week old, a bad marriage this soon couldn’t be happening, she wanted to believe. “Because I’ve always made the right decisions,” she told herself.

While that was true, her choice of men, starting with Alvaro, would prove problematic.

Chapter 4: Cars For Kids

The story of Ben Jr's business, Cosmopolitan Car Service, or Cosmopolitan Cars as it would later be known, is really about Ben and Gen's twins. Because it was wanting the absolute best for them, always, that motivated him when he finally came home from the war. He was sad he wasn't there to see them enter the world, nor witness their first and second birthdays. Ben Jr would work his "ass off" (as he liked to say) for decades making up for it: He was determined above all else to give them both every advantage.

And he was born an entrepreneur, like his father, but also a natural leader and manager. That was about pay dividends.

As babies, Connie and Eli were the exact opposite of what they'd become. She was a royal pain, never sleeping through the night, while, except for feedings, Elias did almost from birth. As toddlers, she screamed and yelled, while Elias was calm and thoughtful. It was not until their father returned that they would assume their future roles, he being the problem, she the apple in everyone's eyes. It was like a switch had been thrown, and nobody could ever explain it.

But presently, almost at the end of World War II, along with doing without because of shortages and rationing, Genevieve Spencer was also raising their children, alone. Sure, Ben Jr's parents were there, and helped often - especially the doting Chelsea, who absolutely adored her grandchildren - but it was still a burden.

A burden that Gen would complain about forever to those same children and husband, who she could only hope was returning. Indeed, her anxiety regarding his return made things worse than they already were.

Which to Gen in the spring of 1945 was hard to imagine. The babies, the worry, Hitler, the Japs, everything - she found it all too much. She was determined if he did ever come back, she'd never let him or the children forget what they had done to her.

Ben Jr did come home and the young Spencer family was reunited. The children, while not old enough to really understand, were still glad their mother seemed happier, and loved their new daddy. The first few weeks were a blur and bliss for everyone.

And Genevieve was indeed happy. But like always, it never lasted, and she would often make the family's life miserable with her cutting remarks and habit of placing blame for her problems everywhere except where it belonged.

Upon Ben Jr's return from Germany, his father encouraged him to take it easy, help out in the shop when he felt like it, and get to know his kids and wife again. Ben Sr by now was flush with cash, having landed a lucrative food supply contract for serving sandwiches to GIs departing on trains from Pavonia, so he told his son to "take as much time as you need." It was a luxury his son would use wisely, and one few other returning GI's enjoyed.

A couple of years passed, with Ben Jr quickly returning himself to his father's store and the minutia of running a gourmet sandwich shop in Hoboken. He thought about going back to Rutgers, but it was after this parade, on Memorial Day 1949 that Ben's future would become more clear. It was then, and for an unusual reason, Ben decided to pursue a particular line of work.

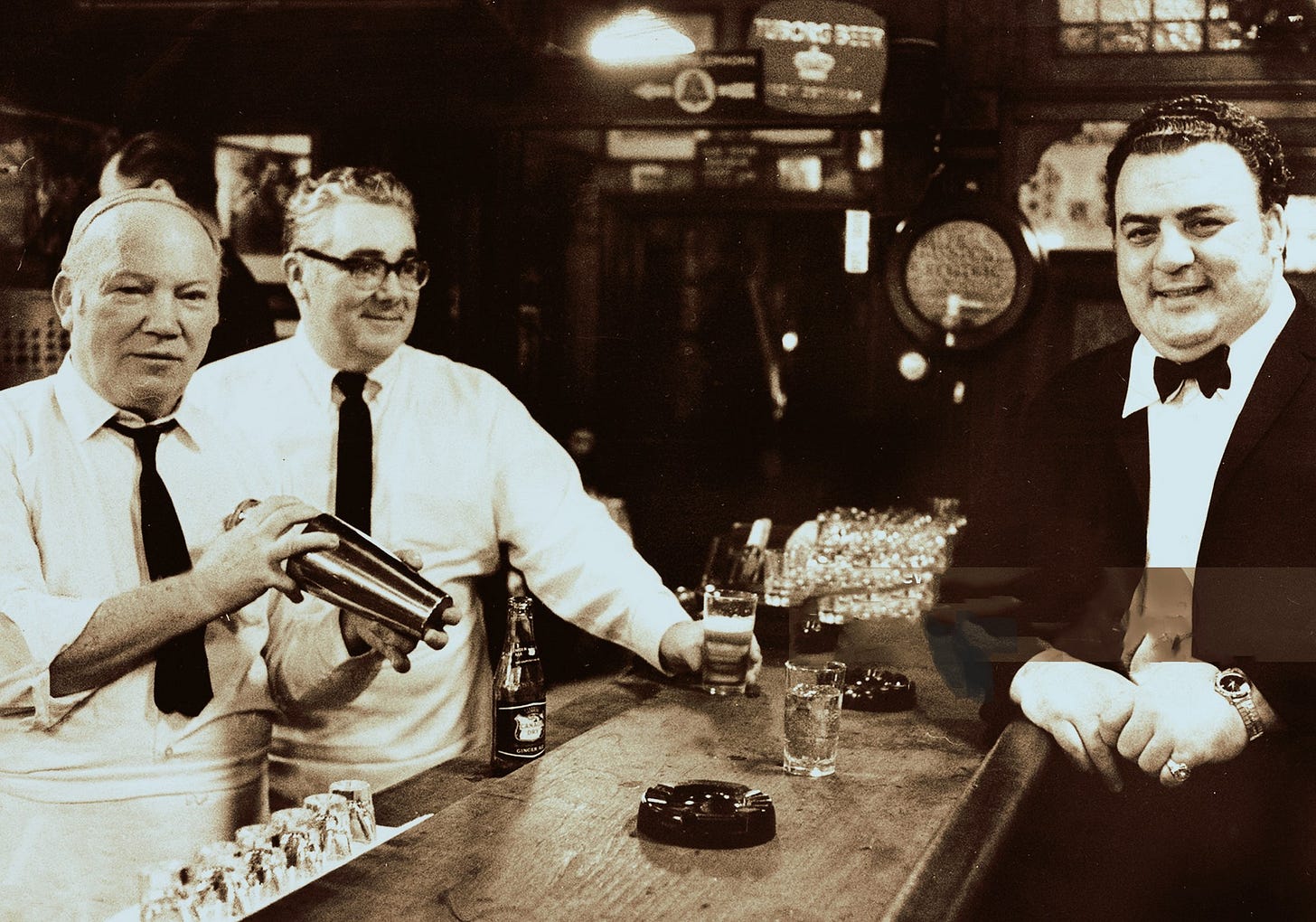

Because he went to Luizzi's Tavern afterward. Now owned by Gio Luizzi's son and Ben Jr's longtime pal Pete, who had been excused from serving in the war due to his bad leg. Which earned him the nickname "Gimpy" around his bar, a popular place for Italians and others seeking a classic watering hole. It was at 2nd and Jackson.

Ben Jr walked in, and said, "Gimpy, what a day! It's got to be a shot and a beer!" It being Memorial Day, his money was no good in a bar full of proud Italian Americans. Ben was a couple of drinks in, and after talking about how they both didn't like President Truman, Pete started talking business. The jukebox was, as usual, playing Hoboken's very own son.

"Hey, listen. My Uncle Paulie tells me the smart guys are buying limos so the swells don't have to take a taxi. Go figure!" Pete, whose leg allowed him to avoid the family business of La Cosa Nostra the same way it got him out of the army, was, with Larry Weinberg, Ben's best friend. Ben knew Pete had a way of predicting the future, mostly because his Uncle Paulie Luizzi was a caporegime in Joseph (“Joe Bananas”) Bonanno's crime family and thus seemed to know everyone and everything.

Yet because of Ben Sr's relationship with Gio, and then Ben Jr's with Pete, the Mafia left the Spencers to themselves. It was a huge advantage in a city and country increasingly run by the mob.

But the Mafia would prove to be excellent customers for Ben, now obsessed with starting what he called his Cosmopolitan Car Service. He was a "car nut" (as they were being called now) from his earliest days, when he vividly remembers them terrifying the horses they were quickly replacing. He had managed his father's store for years, and knew his way around a carburetor. And in the army, he had learned the value of service, dignity and respect. He hoped it might even help Gen - trained as a bookkeeper, she could do the accounting and it would get her out of the house.

And most importantly, that past winter while deer hunting with Gen's relatives at the River Ridge Club outside of Tupper Lake, Ben Jr learned he had a patron. A wealthy Laroux in-law, one of the largest heating oil and gasoline distributors in the Adirondacks, had committed to funding any business that Ben Jr wished to start. His reputation for business acumen was already well-known throughout the family, and now a decorated war vet, it was one of several offers of employment or investment interest he had received.

That is the somewhat unlikely origin of a company that would make him quite wealthy, and allow him to provide for his family the way Ben always wanted. Which was first-class.

During the war, he had come across two different vehicles that would inform his future decisions, car-wise. First were the massive Mercedes Benz sedans he had seen upon arrival in Stuttgart, which his regimen had captured. There was something about their presence that made a permanent impact on him, but it would be years before he'd realize his dream, formed then, of owning a big Benz.

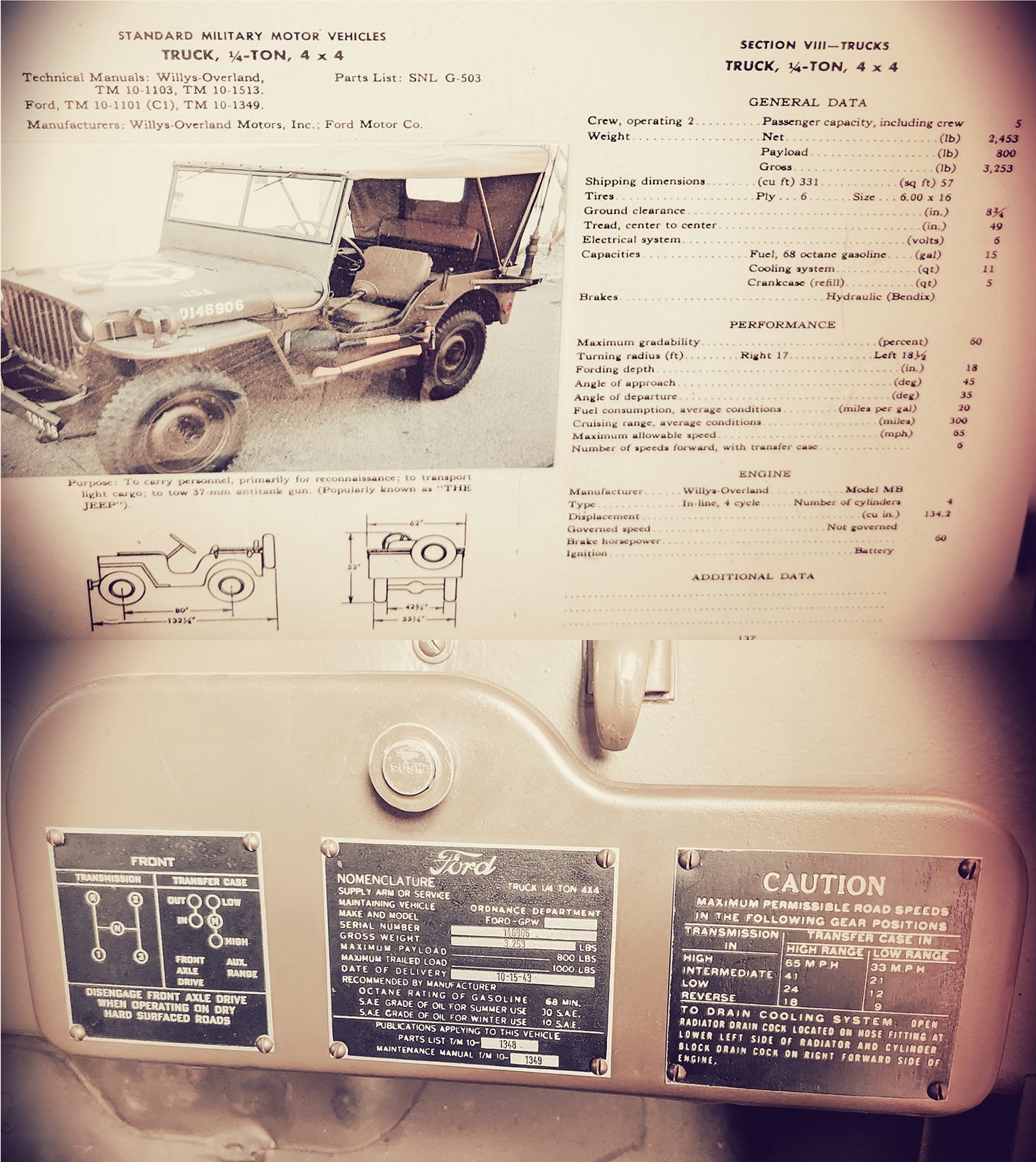

The war also had a more practical impact, vehicle-wise. In Germany, Ben's life and that of 2 others were saved because the "Jeep" he jumped into was drivable despite its damage, and they were able to speed off moments before a mortar landed - and killed several fellow soldiers. Knowing it had been made by Ford, he would be a Dearborn man for the rest of his days, and proudly displayed what others found boring. If they only knew.

So when it came time to buy a car for his company, Ben knew it had to be a Ford. And not just any Ford: Ben would always buy Lincolns.

He started the company in 1950, and copying the first market entrant, J.P. Carey who was driving people from the New York Central's Grand Central Station in a fleet of Cadillacs he had leased (from a Mafia-controlled dealer, at their direction), Ben would focus his attention on his favorite building in Manhattan, the Pennsylvania Railroad's magnificent, if fraying, Penn Station. Along with Grand Central, it was the hub of New York and thus the world, and Ben thought (very correctly, it would turn out) the wealthy travelers using the station would want a stylish and professional option, beyond a taxi, which was neither.

Although Checker was starting up their limo division and operating at Penn Station, critically, Uncle Paulie Luizzi kept Carey at Grand Central as a favor to his limping nephew. He also made sure Ben Jr would not be shook down by anyone in his or the other 4 New York City crime families through the years. Yet the Spencers were protected as if they were indeed paying pizzo - protection money - like J.P. Carey had to. Ben just agreed to fair pricing for limos for the top guys in all of the City's Mafia families for their non-criminal nights out.

In sum, it was a unique opportunity, and Ben was prepared for it: He had made his own luck.

This was the very first car in a fleet that would grow to dozens in later years. It was, appropriately enough, a Lincoln Cosmopolitan.

Ben would need a garage with plenty of space, and he found the perfect building, conveniently down the block from a Gulf station, at 97 Charles Street, near Hudson, in Greenwich Village. It gave him good-enough access to Penn Station and the rest of midtown, but also allow him to serve Wall Street out of the same garage, which would later turn into a gold mine for him. And it was an easy ferry or subway ride from Hoboken.

Of lesser importance was its proximity to Julius', one of Ben Jr's favorite bars when he was drinking with particular friends in Manhattan, although he certainly didn't tell anyone.

Ben Jr was CC's original driver, but that soon expanded. Wife Genevieve did the books and managed bookings (at least in the earlier days), but Ben still needed someone to take care of the company's most precious and expensive asset: its cars.

In a hire that would pay dividends for the company's entire existence, Ben, like his father sympathetic to all minorities, hired a Negro mechanic to take care of the car and then cars. Marcus Howard was only 22 and just out of the service like Ben when he became employee #1. He would go on to become his right hand man and enable Cosmopolitan Cars to develop a sterling reputation for giving its customers "the perfect ride," which Ben set as the only acceptable standard.

Indeed, by 1959 when Ben placed his biggest order with Lincoln to date, he had a total of 5 Negroes working in his shop. He, Gen, his secretary Gladys, and the drivers were the only white faces, which some found odd - but the condition in which the cars were kept spoke for itself.

It had been an advertisement that had convinced Ben to make the sizable investment; it was exactly how he saw himself, his drivers, his cars, and his business. It was these cars when he first stopped plastering his company's name on the side.

He also dumped the word "Service" from their name and added an "s."

Cosmopolitan Cars' new limos would set a standard across a booming Manhattan, and in the 1950s and then into the 1960s, Ben Jr's success allowed him to give everything to his children and wife Gen. Country clubs, nice clothes, vacations in Europe: He did it all for them. In return, he got to run his business as he pleased, including selecting the cars for his drivers, one of his favorite parts of the job.

But while Ben found the lines of the 15 new 1959 Mark IV Continentals he had ordered sleek and modern, Gen developed a real hatred for these cars. Ben suspected why, but would not know for certain until reading her suicide note in a few short years.

Chapter 5: A Car (& Much More) For a Kid

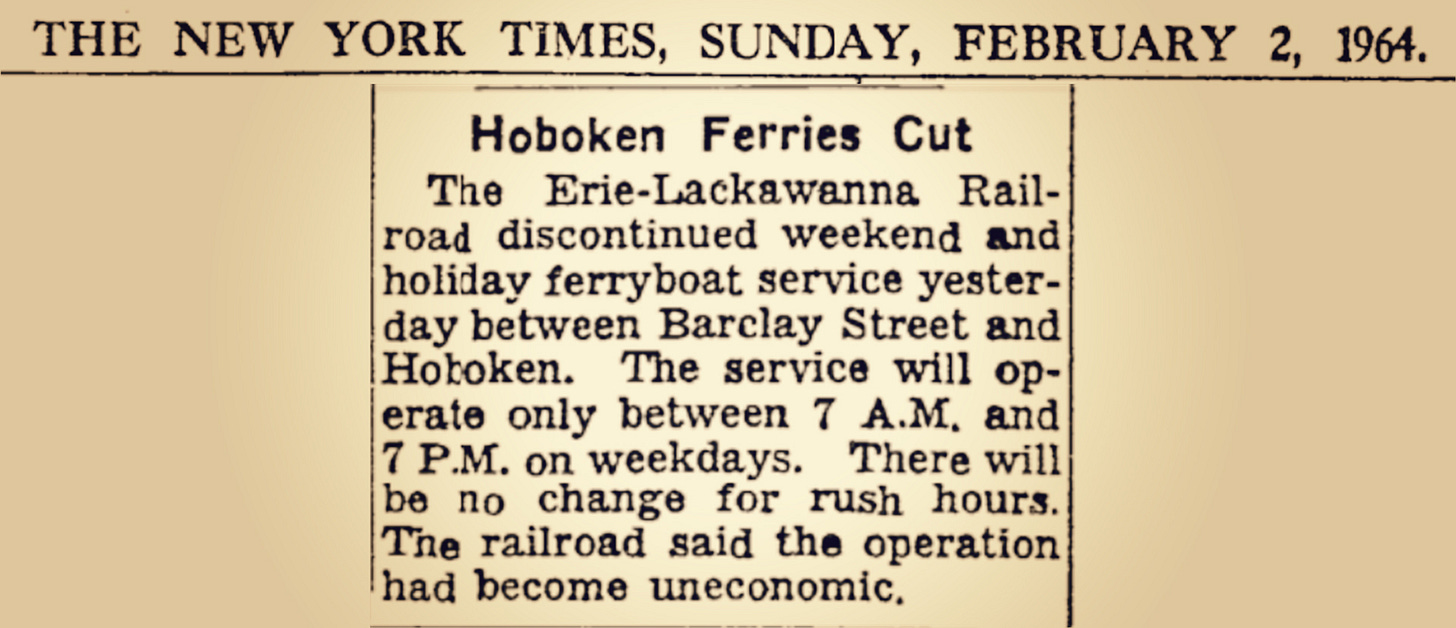

As Elias walked to the sadly deteriorating Hoboken Terminal and its dwindling ferry service, he glanced towards downtown Manhattan. Everything seemed to be changing, for him, for his surroundings, and for the United States.

This was captured by the front page of the previous day’s paper, which Eli had left abandoned on his doorstep and not seen.

But he did see the ongoing abandonment of dock after dock, pier after pier, on Hoboken’s once-booming waterfront on this walk, and on many before. Hoboken by 1964 was a shell of its former self: Deindustrialization and the introduction of containerized shipping appeared to be diseases from which the city would never recover.

As his ferry made the short ride to Christopher Street, Elias considered the city and what lay ahead of him. Even on a bluish-sky day, New York City had an old, tired feel and somehow, only 21, he felt the same. Like Hoboken and lower Manhattan, Eli needed a major rebuild.

He stepped off the ferry, and the noise of the city enveloped him immediately: car horns punctuating conversations and women's heels clacking on the pavement, mostly. Well, that and the distant strains of The Beatles' "I Want to Hold Your Hand."

A young secretary named Beverly Booth, walking to a subway and her midtown job at J. Walter Thompson, was clutching a transistor radio, and the local stations were playing that song every 20 minutes or so. They’d be making their American debut on The Ed Sullivan Show in just a couple of weeks.

Change was everywhere, and it wasn’t just music that was transforming. Since JFK’s murder in Dallas late last year, President Johnson announced his War on Poverty and there seemed to be real movement on civil rights. Negroes were now openly demanding equality and justice, and a final end to the defacto Jim Crow world still in existence. Everybody Elias knew wanted that, too, and they likewise held people like Dr. Martin Luther King Jr in the highest regard.

It was one of the reasons Alvaro’s “white nigger” crack made no sense.

“What did that even mean?” he said out loud to no one. He paused momentarily outside his father’s hulking garage on Charles Street, nervously adjusting his pea coat against the winter chill, even though he was about to go inside. He knew he’d be out of a job within a few minutes; what he didn’t know were his father’s terms.

Since making a huge scene at his sister’s wedding a little over a month ago, his behavior had only deteriorated further. The holidays were one big boozy blur, spent at various watering holes in Manhattan, Jersey City, and back home in Hoboken. As a result, he’d often show up late for work and even as a garage man at his father’s Cosmopolitan Cars, a level of professionalism was not only expected, but demanded. Despite being the white son of the owner, his Negro coworkers embarrassed him, with their punctuality, attention to detail, and positive attitudes. Ben Jr's son Elias, in early 1964, had none of those attributes.

And then there was the accident just a couple of weeks ago. In a family limousine.

"Hey, Eli, did you hear about our boy," Marcus Howard asked Eli as a greeting as he walked through the garage to his Dad's office in the back. He had always been one of Elias's favorites, first when he would hang around the garage has a kid, and now as a fellow worker. Marcus was referring to Joseph C. Thomas, a friend and neighbor of his; pending confirmation by the Senate, he was about to become the first Negro postmaster of Englewood, NJ.

Elias briefly thought about how quickly things were moving for Black people now, but his attention returned to what was about to happen.

“Sit down, son,” Ben Jr said to Elias, and gestured him to one of the two facing leather sofas. Like its resident, Ben's office was immaculate and stylish, more so when one considered it was in a very busy garage full of limousines being readied for their next missions.

Despite the day’s gravity, Elias stifled a laugh at his father’s lack of irony: He had proudly hung in his office the poster Connie had sent from her honeymoon with Alvaro.

Ben Jr studied his only boy, whom he adored. What Eli had seen him doing in the locker room at Glen Ridge Country Club the summer before his senior year in high school had damaged him, so Ben had given his son chance after chance after chance. Plus, he had kept his mouth shut and kept Ben Jr’s secret. Indeed, that eventful day and night had not been mentioned since.

But Eli’s erratic behavior had gone too far. It was only through family connections a nasty car accident in Manhattan, with Ben at the wheel of a family limousine and flask in hand, was swept under the rug. And like at Fairleigh Dickinson, and it was only by sheer luck someone wasn’t badly hurt or worse.

Ben couldn’t fully know what his son would do after getting a pink slip from the family business, bribe or not. Heck, he and Connie literally took their first steps on the garage’s concrete while their mother did the books, and now Eli was getting fired?

He had known it was going to take tough love and a lot of money. But since Ben had plenty of the latter, his son’s recovery and getting him on a path to some kind of future beyond aimless drinking was all that mattered.

That message came through loud and clear to Elias when he heard his father’s offer. Typically formal and polite in public, in private and when agitated, like now, his mother’s foul mouth in him emerged. He was very stern but was not yelling.

“Elias, you are a fucking shit-headed, drunken asshole. Time after time, you have fucked-up every chance I and your mother - rest in peace - have given you to turn things around. FDU is a Goddamned country club, and you fucked that up. And now? You’re either at our real country club, boozing, in town, boozing, or screwing up here at the garage.

“Put simply, you are a complete and total mess. But I love you. And I know how what you saw at our club hurt you. I want to make it right.”

He didn’t want the focus to be on him, so he immediately asked, “Eli, do you want my help? Son, you really need it.”

“Dad, I know,” Eli said and he started to break down.

“It’s just that for a couple of years now, I’ve not understood who you are and if you and Mom were even true or just an act. Now she's gone, and I'll never know. And if you two were an act, isn't our whole family an act? I don’t understand and it’s making me crazy. I know I’m drinking to pretend I don’t know that you like to have sex with other men. Dad, it’s disgusting and it makes me sick.”

“Elias, this is not about me. I apologize but I am not going to have my life ruined by you or anyone. I am going to help you and I am going to do so much for you that I think you’re going to want to keep our secret.” Ben was speaking as if he already knew the outcome, however strife the moment was.

“I can’t go on. I can't live this lie for you.”

“Eli, you must. I think when you hear what I'm offering you'll see how this is good for both of us.

"First, you’re going to that Towns Hospital on Central Park West to dry out. You’re going to be there for however long it takes.”

“What?”

“Shut up - it gets a lot better. When you prove yourself there, I have a job lined up for you, and I am putting you in your own apartment on - wait for it - Park Avenue. Right in Murray Hill, 34th and Park! All expenses paid. Well, as long as you agree to see a psychiatrist every week, and don’t fuck up at work.”

“What is the work?” Although Elias - typically among the smartest in any room - already knew it wouldn't matter. Even with the next piece to his father’s bizarre puzzle.

“Ha! That’s the best part: I talked to Eddie, and as a personal favor to me, you’re going to work for our largest competitor, the King of Caddies, Carey Limousine! You’re going into their driver training program and you’re going to chauffeur New York’s wealthiest back and forth from Idlewild and LaGuardia - in those Goddamned fucking Caddies!”

"Drive for another company? What? I've never driven and I don't want to."

Ben had already been laughing out loud at even the idea of a Spencer - a Lincoln and now Mercedes house through and through - driving a Carey Cadillac, no matter how pretty he thought they were.

Then his father's tone suddenly turned serious. "Son, you are one step away from either jail or the morgue. You have zero choice."

Elias didn’t react. He couldn’t, because his father kept going, and what he said next was so outrageous, he sat there, too stunned to speak.

“But Eli, there’s a very special part to my offer. You know that giant Mercedes limo I ordered last fall for Cosmo? Well, it’s arriving pretty soon, and” Ben paused for effect, but then continued, “it’s yours. I am giving you the most expensive car in the world. But only kind of.

“You only will get the keys from Ed Carey once a month, to use with really special clients - I mean these will be the biggest of the fucking big. You’ll give him the keys back at the end of your shift, and the car will be kept very secure at Ed’s. It will be serviced on my dime - I don’t want those Caddy grease monkeys at Carey touching our Benz. And only you will drive it.

“And I have an even bigger idea for you. I want to send you to England in a couple of years to Rolls Royce for that chauffeur class they have. When you come back, you’ll have ‘graduated’ and you’re on your own. You can leave Carey. The Mercedes, taken care of, should last forever. I’ll put the title in your name at that point. Perhaps it will make sense then for you to come back here and take over. You know I've always wanted that.

"My stupid offer to my fucked-up son is for that. I want you to take this over, and if and when you do, I will want you to have the most knowledge of anyone in the industry. Having grown up here, driven for Ed, and then being trained in Crewe will do that. We'll still have the best cars. You'll certainly have the best car. Wait to see the Benz.

“But fuck up, even once, and our entire agreement is off, I will take the car and the apartment. You'll have to make it on your own, at Carey or wherever. Frankly, this is so nutty generous, if you fuck this up, my conscience is clear and I will not care one Goddamned iota what happens to you.”

Ben Jr stood up and walked towards his office’s fireplace. In his impeccable dark gray Botany 500 suit, crisp white shirt, narrow silk jacquard tie, and cuff links, even Elias - who’d observed his father’s sartorial habits his whole life - was impressed by his elegance. In the most inelegant of places: a limousine garage in the New York's West Village.

Ben then turned around, stared directly at his son, and said, “Do we have a deal?”

Elias’s head was spinning like a top. His father had planned an entirely new future for him, and it was the most bizarre and generous thing he'd ever heard.

Dry out at the most exclusive drunk tank in the City. Free apartment in Manhattan, walking distance to the Carey garage near Grand Central. New, salaried job with the best outfit in town. The chance to drive the best car available, get the best training, and then be able to have it all to himself before turning 30? Just by keeping quiet about his pervert father? And at the same time, being able to keep his own secret: his unintended role in his mother's suicide?

“Dad, I don’t know what to say. It’s the craziest thing I’ve heard. But Mom’s g-g-gone," Eli stuttered for the first time in his life but then continued, "and I know you’re on your own road so to speak. I’ve got to get it together. I want to quit drinking, and right now, I am completely lost.

“So, yes. Yes, Dad, thank you for saving me. When do I start at Carey? When do we get our hands on that big Benz? And when can I move to Park Avenue?”

Damn, I spoiled this boy rotten, thought Ben Jr.

“Talk to Gladys,” Ben Jr said, gesturing at his secretary on the other side of his office’s glass and his confidant of over 10 years. “She’s got a packet of information for you - everything’s in there. You’re to report to Towns first thing tomorrow morning. Consider yourself fired. And sober.

“Elias, don’t fuck this up. This is it.”

"Sure, Dad. Hey, what's the suitcase for? Going somewhere?"

By this point Ben Jr was such a good customer of Lincoln's, they were flying him to Chicago on Ford's new corporate jet, so he could see in person their next limousine, manufactured by Lehmann-Peterson there. He'd be going to Teterboro in a couple of hours.

Ben would order 20 of them on the trip, and looked forward to never seeing a 1959 Lincoln again.

"Hi Gladys. Please turn that down," Elias said, gesturing at the big radio on her desk. "Dad said you have a packet for me?"

"I do, and what's the matter, Eli, don't you like that song? My daughter loves it."

"I've already heard it too much," he answered, taking the large envelope from the sturdy Gladys, and headed back to the ferry and Hoboken. For one of the last times; Benjamin Elias Spencer III would soon be a Manhattanite.

He would first have to get sober. And then perhaps accept his father for who he is?

Gladys was able to catch the end of the song after he left; she found it fun.

Chapter 6: Doors Opened and Closed

A Day at Glen Ridge Country Club

The four Spencers, parents Ben and Gen, and their twins Connie and Eli, arrived around eleven on Saturday morning, about when the Glen Ridge Country Club came alive with both the thwock of rackets striking tennis balls, and the first martinis of the day. Their club, a 35 minute drive northwest of Hoboken, had been the family sanctuary from gritty Hoboken ever since Ben Jr insisted they apply for membership 5 years previous, in 1954, after Cosmopolitan Cars had really taken off.

"It'll be good for the business," he said then, and as was often the case when it came to business, he had been correct. It allowed him to add prominent businessmen and academics to his clientele, which to date had consisted primarily of America's biggest mobsters. It was through friends of friends at the club that he would find himself and those in his employ transporting the world's most brilliant and wealthiest.

Ben pulled his Continental Mark II into a space near the entrance, not hiding his satisfaction that the spot afforded both shade and prominence. The automobile itself - midnight blue, gleaming with wax - announced what his wife's quiet sighs and the twins' high school senior indifference did not: we are here, and we have arrived. He couldn't resist when Lincoln offered him one at dealer cost a year ago.

"Well," Ben said, turning off the ignition and adjusting his straw boater in the rearview mirror. "Here we are."

Genevieve said nothing, her gaze fixed at the modern clubhouse, opened just two years ago, after the tear-down of the original colonial one. They all knew she was counting the minutes until she could retreat to the women's pavilion, with its cool marble floors and cold stares and colder vodka.

The twins sat equally cold in the back seat, sixteen years old and already masters of the carefully crafted sulk. Elias with his nose buried in a paperback novel about an airline pilot, Connie braiding and unbraiding a strand of her dark hair, both pretending they were anywhere but here, in this parking lot, with these parents, on this particular Saturday in July, in this particular part of North Jersey.

"For Christ's sake," Ben muttered, "at least pretend to enjoy yourselves."

The twins exchanged glances in their private language, the one they'd developed and refined through almost seventeen years now of watching their parents' marriage slice itself thin like cold cuts in their grandfather's delicatessen.

With their day bags and golf clubs, they made it inside, but soon went their own ways, first to their lockers and then elsewhere.

Ben found his regular foursome, Tom Frederick, Bill Cameron, and a rotating fourth who was today a ruddy-faced man named Connolly. They were off to play 18 and would be gone for 4 hours or so. The twins headed downstairs to go outside while Genevieve went to find her bridge club.

The pool at Glen Ridge Country Club was Olympic-sized yet still often crowded on weekends. Elias found some empty loungers at the end and sat in one, after spreading out his towel. He flicked on his omnipresent transistor radio, spun by WINS and WMCA and landed on WMGA, which he liked because they were more likely to play his favorite pop tunes; one was playing now.

"Your mother's at bridge," Connie announced, appearing beside him with two bottles of Orange Crush, already damp from the humidity. She wore a red bathing suit with a modest cut that nonetheless drew glances from boys of various ages. Connie had matured into a prettier version of both her mother and father. She had been dating the same boy since her sophomore year, while Elias, equally attractive, had - and typically - done the opposite. Presently, he was unencumbered, but looking - Eli often met girls from other schools and towns at the club.

"She told me to watch you." Elias was typically good for sneaking at least 3 or 4 drinks from the pool bar. At times, they'd even serve Eli directly, at least after a nod from his father.

"I'm watching her," Elias replied, taking the lemonade. "Same difference."

They observed Genevieve in her wide-brimmed hat at a table beneath a striped umbrella. The bridge club had decided to play outside today. Gen clutched her cards, and said words they couldn't hear but knew by heart:

"Two spades." "I'll bid three hearts." "Partner, why did you lead with diamonds?" Their mother played bridge like she was excavating for something lost beneath the cards.

"She took another pill in the car," Connie said quietly. "When Dad was getting the clubs from the trunk."

"I know," Elias said. "I saw her."

They sipped their orange sodas in silence, watching the parade of country club life unfold before them. It was typical of so many of their past summer days over the years, although they both knew the easy life of a teenager was ending, with their final year in high school approaching. Then: Adulthood, and while Connie seemed ready, it was a toss-up regarding Eli.

"What a day," Connie said in their father's voice, a perfect mimicry down to the way he'd clear his throat between sentences. "What a perfect goddamn day to be alive."

Elias snorted Orange Crush through his nose, and they both dissolved into laughter that drew annoyed glances from the cabana area. They made exaggerated stares back and left for the pool. Both twins took real pride in being smart-asses - even the otherwise-perfect Connie.

"Are you two joining us for the club dance next weekend?" Eileen Cameron appeared beside them in the pool, her voice syrupy with false hospitality, and shoulders red from a lack of suntan lotion. The daughter of their father's golfing partner, she was a year older than the twins and already possessed her mother's talent for nosiness disguised as pleasantry.

"I'm not sure," Connie replied noncommittally.

"You really should," Eileen continued. "Princeton boys come down for it. Yale too." Her gaze slid to Elias. "Though I suppose you'll be off to Rutgers like your father - didn't he go there before the war?"

"Yes, but for me, it's Columbia, actually," Elias replied, watching with satisfaction as her perfect eyebrows lifted a fraction of an inch.

"How interesting," she said, trying to appear unimpressed. "Will you be staying in the dorms or . . . "

"Commuting from Hoboken?" Elias finished it for her. "I just might."

Eileen's smile tightened. "Well, do consider the dance. Connie would look lovely in blue, don't you think?"

After she drifted away, Connie kicked water at her brother. "Columbia? When were you going to tell me?"

"I'm not," Elias said. "I just wanted to see her face." He looked at his sister and they both burst out laughing.

And not for the last time that day and night. Because the country club scene in North Jersey in the summer of '59 struck both of them as very funny.

---

Genevieve excused herself from the bridge table after losing the third rubber. The other women - Mrs. Bentley, Mrs. Weintraub, and the widow who called herself Miss Burns - watched her go with a look of disdain and disgust. Odd, since they were all supposedly the best of friends and had played bridge together for years.

In the women's lounge, she locked herself in a stall and sat fully clothed on the closed toilet lid. She opened her purse and removed the amber bottle of pills, shaking one onto her palm, and then, after consideration, a second. The doctor called them "mother's little helpers," a phrase that made her want to drive her fingernails into his self-satisfied face.

What did they help with? They helped her ignore when Ben . . . strayed. They helped her forget, for stretches of blessed numbness, that she had once been Genevieve Laroux of Tupper Lake, New York, before she'd fallen for the stylish and charming Ben at Rutgers. Before she got unexpectedly pregnant, which was bad enough, but twins? By herself, with her husband at war? Gen never let it go, even now, 17 years on.

She swallowed the pills dry, a skill she'd perfected.

Outside the stall, she heard female voices entering the lounge.

"The Spencer twins are peculiar, aren't they?" one said.

"Well, consider who raised them," replied another. "Her with her pills and him with his - well, you know."

"The girl seems nice enough, but the boy . . ."

Genevieve leaned her head against the cool metal partition. There was a time when such talk would have sent her storming out of the stall, French-Canadian and Adirondack dignity aflame. Now she only felt a muted curiosity, as if they were discussing characters on a TV show she only occasionally watched.

---

Elias had been in search of his sister when he made the wrong turn. The corridor behind the men's locker room was poorly lit, institutional in its stark white tiles. He was about to turn back when he heard a sound - a muffled voice, his father's voice, though pitched differently than he'd ever heard it.

He hesitated, then moved toward the partially open door at the end of the hall. A storage room of some kind, lined with shelves holding folded towels and swimming supplies.

Through the opening, he could see two figures. One was his father, still in his golf clothes, his back to the door. The other was Mr. Connolly, the fourth from his father's golf game.

What happened next burned itself into Elias's consciousness with such clarity that he would revisit it in dreams for decades to come: The way his father sank to his knees, the way Connolly's hand found the back of his father's head, the unmistakable rhythm of what followed.

Elias backed away. When he reached the main corridor, he turned and walked swiftly toward the pool and the tennis facility beyond it. His heart was pounding and his mind scrambling to reconcile this new information with everything he thought he knew about Benjamin Spencer Jr., owner of the second-most successful limousine company in Manhattan, driver of Lincolns, husband of Genevieve.

His father.

---

Connie found her brother by the tennis courts, watching a doubles match with an intensity that suggested he was memorizing something essential.

"Where'd you go? Dad's looking for us," she said. "It's almost dinner time."

Elias said nothing, his eyes fixed on the players, seeing none of them, and barely hearing his sister and best friend.

"What's wrong?" Connie asked, the twin-sense between them prickling with alarm.

"Nothing," he managed. "Just thinking."

She studied him. "You're lying. I can tell when you're lying."

"Drop it, Connie," he said, his voice sharper than he intended.

She recoiled slightly, hurt going across her face before hardening into anger. "Fine. Be that way. Fuck you, Eli. But we need to change for dinner."

They walked along the manicured path toward the clubhouse, a new silence between them, not the comfortable shared quiet of their usual communication but something barbed and unfamiliar.

"Is Dad a normal person?" Connie asked suddenly, although she had no idea what she was actually asking.